查看完整案例

收藏

下载

翻译

Moving to Mars opens at Design Museum London, aiming to answer some of the big questions around moving to a different planet

Enter a simulation of the red planet at the Moving to Mars exhibition at the Design Museum. Photography: Felix Speller for the Design Museum. With thanks to Oxygen Model Management.

The European Space Agency often get asked why they want to explore Mars. The first answer is, because it’s there, and secondly it has a huge amount to teach us – mainly concerning the evolution of the solar system, rock formations, greenhouse effects. But what does that mean for you and I, and the next generation?

The question of actually inhabiting Mars offers up a whole new set of queries – psychological, philosophical and practical ones. How do we stay human on a place not designed for humans? And, how are we going to stay safe and sane on a nine month journey to Mars? At what point do we become Martians? – these are some of the complex questions the exhibition asks through prototypes, research projects and products by scientists and designers.

The first part of the exhibition sets the scene with the history of our human knowledge of Mars and recorded resources, from Giovanni Schiaparelli’s drawings from the Brera Observatory in Milan to Percival Lowell’s 1896 book Mars. Popular culture references like copies of Authentic magazine to Paul Verhoeven’s film Total Recall set in 2084 capture our fictional fantasy accounts of the planet too, but soon, sci-fi turns to near future reality.

Looking at vacuum packed food by NASA and watching videos of astronauts floating in a rocket suddenly feels like watching an in-flight safety video. Designer Konstantin Grcic has designed a table for in-flight dining at zero gravity for the ride. While Anna Talvi, who works between biomedical science, material science and design, presents a bodysuit made out of a smart membrane that helps humans retain muscle in a microgravity.

Travelling to Mars: Sokol spacesuits, pictured at the Moving to Mars exhibition. Photography: Ed Reeve

But it’s not all slow-mo somersaults and chucking around M&Ms. Lucy McRae’s video work Institute of Isolation questions what might happen when you are confined with a few other people in a small space for a long time. A solution to homesickness might be smelling Talvi’s ‘Earth-memory smell-scape gloves’ that capture the scent of freshly cut grass, and other earthly smells.

It’s mid-afternoon on Mars, when you arrive, and there’s a hazy light descending over a landscape of red rocks near Glen Torridon, a mountain range namedafter its Scottish equivalent. It’s beautiful, but it’s not a sci-fi set. Suddenly, the air becomes thicker, instead of rain shower on Mars, where there is no water, a toxic dust storm descends, and it could last for months.

You take shelter inside your new home, built of compacted regolith, Mars’ loose sandy topsoil. The house has to be gas tight – SEArch+ suggest a high-density polythene lining, while Foster + Partners suggest an inflated inner pod. The exhibition offers up an opportunity to step inside a life-size Mars house designed by Hassell and constructed by ‘swarm robotics’ – a group of collaborative robots. It’s fun, but it’s lacking hygge.

Your new home on Mars: Foster+ Partners’ Mars Habitat, pictured at the Moving to Mars exhibition. Photography: Ed Reeve

There’s a kitchen, a hydroponic farming kit by GrowStack and you can also grow a Mars boot, designed by Liz Ciokajlo and Maurizio Montalti, out of fungal spores. There’s a sewing machine too – designer Graham Raeburn has designed a collection of clothing based upon reuse of solar blankets and parachutes, so you’ll need that when you get there.

While thinking speculatively about Mars, Raeburn’s design process, he explains, was very much tied to the problems we have here on earth too. To avoid polluting another planet, all of his designs are focused on sustainability, re-use and re-cycling. All evidence points to the looming possibilities of Mars travel, but the strength of the exhibition also lies in its ability to show the relevance of the projects back to earth.

Eleanor Watson, assistant curator, explained how the question of ‘being human’ became an open-ended query for the curators, not yet ready to be solved: ‘Does moving to Mars make you a post-human because you are having to adapt your body so much to another planet?’ she asks. ‘Mars has 40 extra minutes in the day. Do you live a normal day and have an extra 40 minutes at the end? Do you stretch the minute? What does that mean to your relationships on earth, your circadian rhythm?’

All these questions feel fairly unnerving and fururistic, but the reality is that most children seeing this exhibition will be able to visit Mars in their lifetime. For their contribution, SuperUber and futurist Thomas Ermacora created a video, Mars 2100 Expedition, to take you on the emotional journey of an astronaut travelling to space, placing you ‘into the shoes (or helmet) of an astronaut in 2100 going to Mars’. Using a first person narrative and animated visuals, the team hoped to create an approachable and accessible insight into that experience: ‘Such a leap for humanity probably shouldn’t be left to a few competing space entrepreneurs and governments to decide the purpose. It is time to ask the public what they think Mars should be about.’ §

Stills from SuperUber and Thomas Ermacora’s Mars 2100 Expedition video piece. The aesthetic of the work is inspired by futuristic comics such as Moebius, with the aim to create an emotional visual narrative that triggers people’s imagination.

Hydroponic farming unit by GrowStack. Photography: Felix Speller for the Design Museum

Mars Habitat by Hassell. Photography: HASSELL + Eckersley O’Callaghan

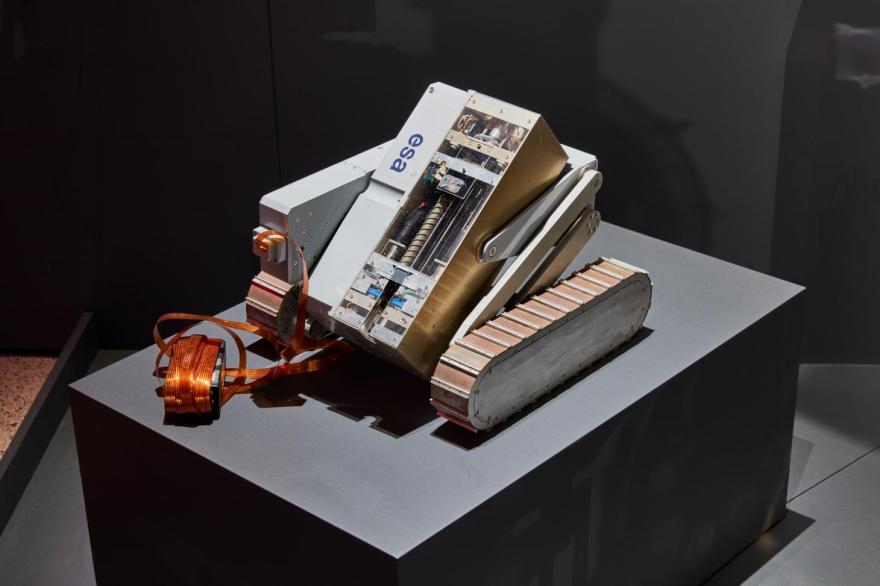

ESA rover prototypes, Moving to Mars exhibition. Photography: Ed Reeve

3D-printed furniture by Nagami, at the Moving to Mars exhibition. Photography: Felix Speller for the Design Museum. With thanks to Oxygen Model Management

客服

消息

收藏

下载

最近