查看完整案例

收藏

下载

翻译

With concurrent solo shows in Paris and London, the Canadian artist is having a moment. We lose our minds, virtually, in the complex, hypnotic art of Jeremy Shaw

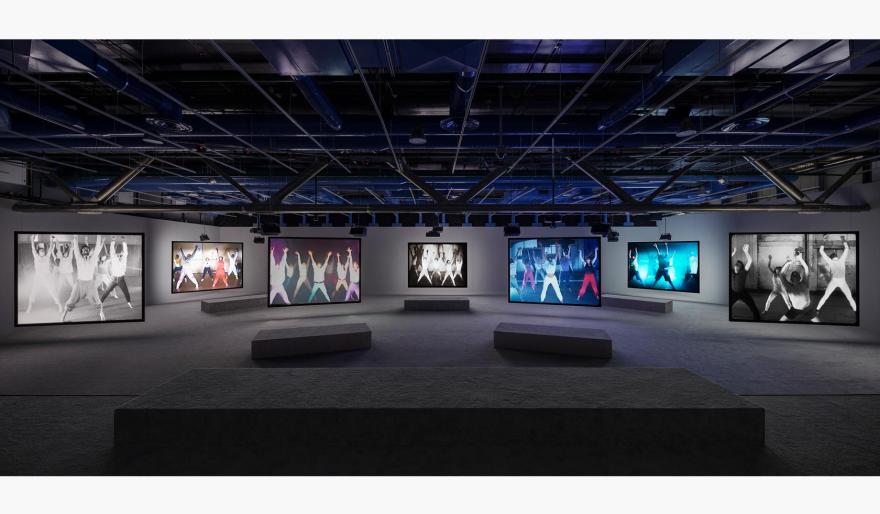

Installation view of Jeremy Shaw, Phase Shifting Index. Photography: Timo Ohler; courtesy Jeremy Shaw and König Galerie

To walk into an exhibition by Jeremy Shaw, we’re asking to get high. We want to find out what gets people high and what defines high ideals.

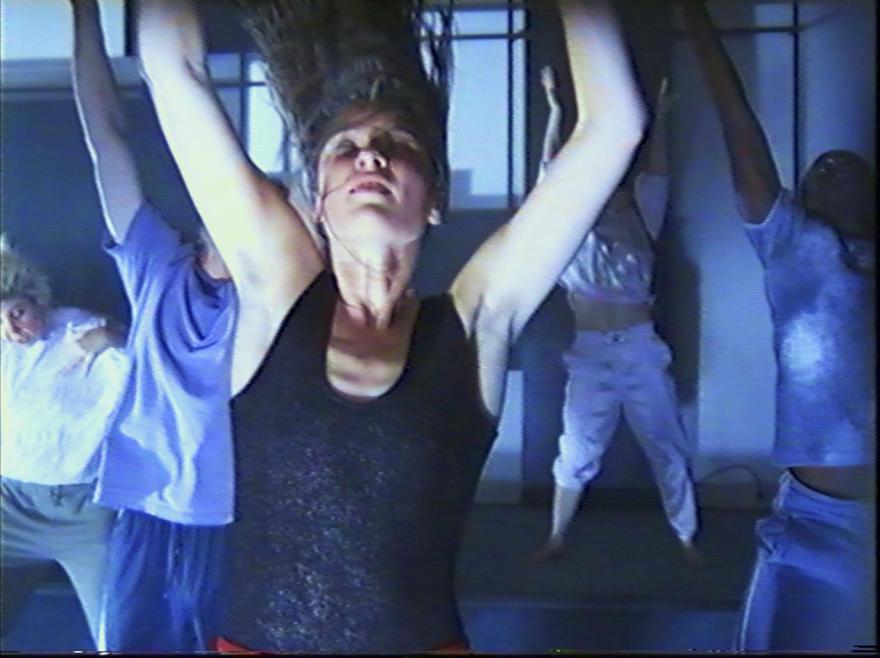

Edging up a claustrophobic ramp towards Gallery 3 of Paris’ Centre Pompidou, there might be a niggling sense of trepidation. This is a Jeremy Shaw exhibition after all, and they’re never particularly forgettable encounters. Inside the show’s new title work, Phase Shifting Index (part of the museum’s Mutations / Créations programme) are seven screens on which people move, writhe, and dance in singular hypnotic rituals to their own soundtracks. These films feel archival – possibly from the 1950s to 1990s – but are in fact rendered through outmoded, and disorientating use of 16mm film and Hi8 video.

Phase Shifting Index, 2020, installation video. © König Galerie, Berlin

Aurally, it’s almost as overwhelming as Cildo Meireles’ Babel, a towering sculpture comprising hundreds of radios, each tuned in to a different station. Shaw’s environment spins viewers into a state of unease through intense aural overlaps, but unlike Babel and much to our relief, Phase Shifting Index does eventually reach fruition. A crescendo brews, then each strand unites in pure, ‘cross-temporal’ sync – a moment of collective catharsis for Shaw’s protagonists, and for us. ‘I’ve always found that watching people work themselves into a trance has a proxy-like effect on me,’ he explains, ‘that is something that the dramaturgy of Phase Shifting Index aspires to do with those who engage with it.’

‘I’ve always found that watching people work themselves into a trance has a proxy-like effect on me’

Much of the Canadian, Berlin-based artist’s interests fall on the cultural fringes, like rave and techno-era subcultures or 1960s and 70s psychedelia. Belief systems, technology, sociology, mass-consumerism, ludicrous parascience, sci-fi and straight science are all thrown onto a level playing field and spun into Shaw’s academic, fictional web. In an era where distinguishing genuine news from satire, sensationalism from plausible scientific breakthroughs, Shaw’s hypothetical plots suddenly feel quite close to home.

Shaw’s fascination with transcendence can be traced to his roots: growing up with Catholicism, playing games to ‘intentionally black out’, excommunicating himself, exploring spiritual hedonism and toying with limits.

Since the mid-2000s, his ideas have become more intuitive and propositional. ‘My early work followed a more didactic, conceptual approach whereas the newer works are much more alchemical in their combining of various formal, aesthetic and conceptual elements into autonomous wholes,’ he explains.

It’s Shaw’s command of film and deep engagement with his ideas that make his work so acutely disorientating. In 2004, he made the piece that pricked the ears of the art world. In DMT, eight subjects, including Shaw, take the hallucinogen dimethyltryptamine (DMT) on camera. Subtitles capture the detached, incoherent commentary of the corporeal self in an out-of-body experience. As Shaw described in an interview with the Swiss Institute’s Simon Castets and Laura McLean-Ferris, ‘This quickly revealed to me how insufficient language was to elucidate such a mind-blowing experience, with most participants struggling dramatically to put into words the profundity of what had transpired.’

Phase Shifting Index, 2020, installation video. Courtesy Jeremy Shaw & König Galerie, Berlin

Shaw doesn’t need conventional language to transport his concepts; his talent lies in allowing unsuspecting spectators to become integral to the work before they know it. In 2012, for the group show ‘One on One’ at Kunst-Werke, Berlin, artists were commissioned to create a work that only a single person could experience at a time. Shaw’s piece invited a viewer into a chamber where they sat on a chair in a fixed position. A video started playing, which Shaw describes as ‘some dated novelty you might find in a thrift shop discount bin’, riddled with subliminal messaging. If the viewer stood up, the video stopped.

‘The human desire to escape one’s perceived reality and the apparent universality to the phenomena fascinates me to no end’

Shaw’s art grips us through multisensory manipulation, in a similar way that a DJ might command the behaviour of a club with frequencies and subfrequencies. It’s not so much about what we’re seeing or hearing, but how it makes us feel.

Jeremy Shaw, Towards Universal Pattern Recognition (Baptism Bayfront Center, 1982) © Timo Ohler

At König London, concurrent with the Centre Pompidou show, Shaw is having another moment, ‘Selected Facets and Translation’. In the ongoing series, Towards Universal Pattern Recognition, he studies high states of mind through low-tech methods. Multi-faceted acrylic boxes frame and distort archival photographs of people experiencing some form of ‘awakening’, the nature of which is hard to deduce – is it ecstasy, salvation or desperation? A cheerleader clasps her hands and prays, a yogi meditates, someone undergoes psychic intervention and whirling dervishes practice physical endurance to honour their higher power. ‘I’m specifically interested in the human notion of transcendence – of actively searching it out, however one attempts to do so. Be it through dance, religion, drugs, technology, etc. – the human desire to escape one’s perceived reality and the apparent universality to the phenomena fascinates me to no end.’

Lining another wall, his series, Aesthetic Capacity, sees Shaw engage with the Kirlian photography technique. For this, he listened to the 1969 ‘Billboard Hot 100’ and at a particular point in each track, charged his index finger with a bolt of electricity and placed it on Polaroid film. The result is a grid of fingerprints surrounded by a halo-like aura, supposedly an optical snapshot of Shaw’s bodily response to each song.

Jeremy Shaw, Towards Universal Pattern Recognition (Psychics OCT 17 1071), 2018. Courtesy König Gallery, London

The work of Jeremy Shaw can take us to spaces where the inconceivable becomes real for just a few moments, or as one of the DMT participants – mid-drug-induced stupor – uttered, ‘just somewhere completely elsewhere.’ To understand his work wholly might take months of scholarship, but one thing we can learn is to always expect the unexpected. §

客服

消息

收藏

下载

最近