查看完整案例

收藏

下载

翻译

Curator and architect Joseph Grima proposes a new type of non-extractive architecture that does not exploit the planet in his manifesto for the Dezeen 15 digital festival.

The architecture of the future must prioritise conserving the earth's resources if humans are to overcome the evolutionary crisis that they currently face, Grima argues.

"In the face of clear and present danger, we have no choice but to rethink the predatory principles (towards habitat, towards each other) that modern industrial economies are optimised towards," he writes.

"Non-Extractive Architecture is a form of architectural practice which considers the full chain of building's consequences, taking all possible externalities into consideration."

Grima previously curated the Non-Extractive Architecture exhibition and research programme at the V-A-C in Venice and edited a book on the same topic.

Dezeen 15 is a digital festival celebrating Dezeen's 15th birthday. Between 1 and 19 November, 15 different creatives from around the world will propose ideas for making the world a better place over the next 15 years. See the line-up here.

The following notes and reflections on a new paradigm in architecture were drafted by Joseph Grima and Space Caviar during an ongoing research residency hosted by V-A-C Foundation in its Venice location of Palazzo delle Zattere. The residency is a year-long project examining the material, social, economic and environmental implications of architecture as a practice in the 21st century.

Also featuring an exhibition, a series of public conferences and events, research labs, a design studio and materials workshop, Non-Extractive Architecture transforms V–A–C Zattere into a live research platform focused on rethinking the balance between the built and natural environments, the role of technology and politics in achieving such a balance, and the responsibility of the architect as an agent of transformation.

Non-Extractive Architecture: notes towards a new spirit in design

1. The important waves of technological change are those which alter the balance of power between humans and their habitat.

To survive in a hostile and competitive environment, humans developed socio-technical systems - tools that extend their powers both quantitatively and qualitatively. They allowed us to adapt to a wide range of conditions and habitats, and are at the root of our success as a species.

Nautilus Minerals Inc at Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, photographed by Armin Linke

2. Engelbart's law states that the intrinsic rate of improvement in human performance is exponential: throughout the history of our existence as a species, we have kept getting better at getting better. Although progress manifests itself most obviously in technology, the ability to improve on improvements resides entirely within the human sphere. It is part of our nature.

At first, our tools gave us the means to survive on this planet. Later, they gave us the means to prosper; ultimately, to fundamentally modify our habitat. During the Industrial Revolution, we learned to optimise our tools and our economies to maximise their extractive potential. Unaccustomed to the accelerating effectiveness of our tools, we were unqualified – or unwilling – to fully consider their compound effect at a systemic level.

3. We now face an evolutionary crisis: we are unable to biologically adapt to our environment at the speed we are able to transform the conditions of life on Earth.

Getting better at getting better will not on its own be sufficient. In the face of our accelerating technological supremacy, we can no longer afford to simply ask how much it is possible to extract from our habitat; we are now compelled to ask how much it is reasonable to extract. Put differently, in the face of clear and present danger, we have no choice but to rethink the predatory principles (towards habitat, towards each other) that modern industrial economies are optimised towards.

4. Non-Extractive Architecture is an attempt to enact this shift from the possible [i] to the reasonable [i] within the boundaries of construction-related industries.

In recent decades, environmental discourse has created in the public's mind a broad equivalency between ecological responsibility and energy efficiency. This equivalency is false: while efficiency is necessary, it is not sufficient, and rebuilding “efficiently" often simply adds to the extractive load rather than decreasing it.

The reality is that a far broader and more ambitious reassessment of human activities is urgently needed. In the place of energy efficiency, we propose to consider externalities as a metric of sustainability.

In economics, an externality is a cost or benefit for a third party who did not agree to it. An example of an externality is the excessive mining of sand required for the production of concrete, which can alter the conformation of the river bed, force the river to change course, erode banks and lead to flooding, devastating the habitat and livelihood of the local community (human or otherwise).

The costs of this damage, and its consequences, are not paid by either the producers or users of the sand, which is what makes concrete economically viable as a material. Non-Extractive Architecture is a form of architectural practice which considers the full chain of building's consequences, taking all possible externalities into consideration.

Barcelona Pavilion by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe photographed by Armin Linke

5. Architecture's externalities do not necessarily take material form. They are as discernible in the procurement of labour as in the production of material resources.

6. The burdens imposed by these externalities are not evenly distributed. They typically affect the weakest strata of community, society and the species. At a local level, the privatisation of public space in order to reserve it for exclusive use by the most affluent layers of society imposes a hidden cost on those who have no choice but to give it up. At a macroscopic level, it can be found in the depredation of resources that impoverish communities lacking the political influence necessary to defend themselves. At a planetary level, it can be detected in the exploitation of “free market" mechanisms to transfer resources and labour from the South while at the same time offshoring the management and disposal of waste produced in the North.

In this sense, the almost inconceivably complex nature of contemporary global supply chain frameworks is not accidental. By design, this extreme complexity conceals all traces of the unpaid costs associated with “normality" are excised, insulating them beneath multiple layers of physical, social and temporal removal - a crucial precondition for this normality to remain socially acceptable.

Scales of Extraction drawing by Charlotte Malterre Barthes, published in Non-Extractive Architecture volume 1

7. The construction industry's externalities are often concealed by distances in time rather than in space. Non-extractive architecture must fully consider the costs not just for the individual and for society, but also future societies who will live with the consequences of the choices of today's technologically empowered humans.

8. The transition towards a non-extractive architecture is a function of a larger shift in the scope of economies and should be recognised as an opportunity for increased, not diminished, collective prosperity.

Designers have a decisive role to play in envisioning the possibilities of future habitats, and they could start by conceiving alternatives to the radically decentralised geographies of contemporary material production and consumption.

In order to achieve this prosperity without externalising its costs, key phases of the commodity lifecycle (production/consumption/reclamation/disposal) should become a core part of our urban and territorial fabrics.

There are many benefits to designing with the goals of urban self-sufficiency, increased reliance on local production and independence from extended supply chains in mind.

First, it makes the tradeoffs involved in building - both benefits and costs of sourcing a certain material, for example - visible and palpable to the end-user. It vastly reduces the vast web of logistics infrastructure upon which the current system of material procurement depends, which is one of most energy- and emissions-intensive segments of the global economy. It also encourages a richer diversification of human habitats, bringing them back into dialogue with the local climate and local material environment.

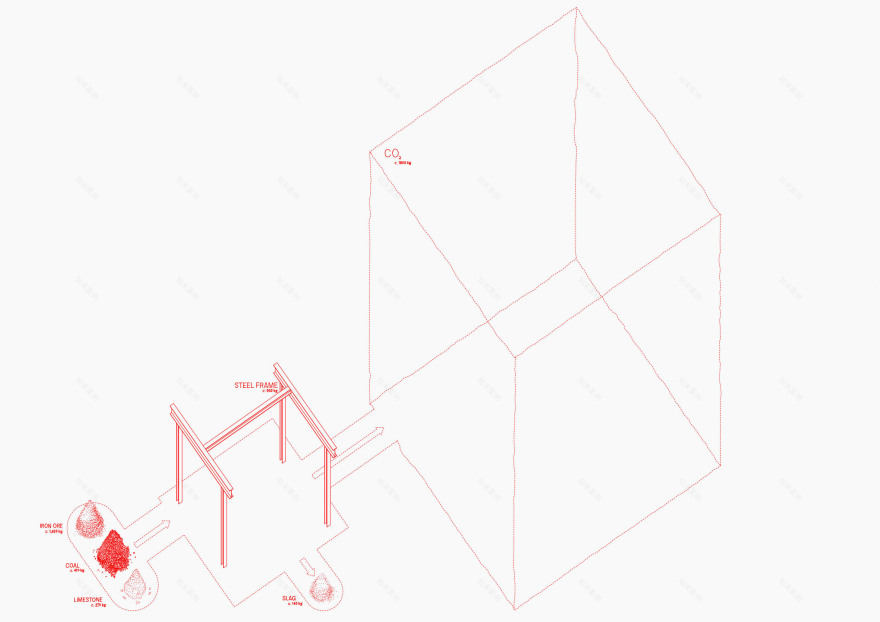

Steel frame drawing by Luke Jones published in Non-Extractive Architecture volume 1

9. The transition towards a non-extractive economy needs the political support of individuals, but cannot be carried out individually. It requires policy frameworks that disincentivize extractivism and its externalities by mandating that costs to the end-user amount to a product's true cost, including all social and environmental costs associated with its production.

In order to create a level playing field between extractive and non-extractive practices, it is imperative that costs are fully accounted for rather than concealed in a distant time or place.

Most of the techniques, technologies and practices necessary to implement non-extractive architecture already exist, but cannot compete in a market artificially skewed by a predatory attitude towards the environment. Such an economic framework could make them viable.

Non-Extractive Architecture volume 1

10. The fundamental principle driving capitalism – perpetual economic growth – is irreconcilable with long-term collective prosperity, and many possible alternative goals exist. The principle of coevolution – an augmentation of human cognitive wealth and intelligence, as proposed by Engelbart – is one example.

11. Non-extractive architecture is not a dogma and means different things to different people in different places and times. Its definition is a (small) part of the collective decision-making process upon which the continued existence of our species on this planet depends.

Above: portrait of Joseph Grima. Main image: oil platforms in Baku, Azerbaijan, photographed by Armin Linke

Writer, curator and architect Joseph Grima is the creative director of Design Academy Eindhoven and co-founder of research studio Space Caviar. Before founding the studio, he curated installations for events including the Biennale Interieur in Kortrijk, Chicago Architecture Biennial and the Istanbul Design Biennial.

Read more about Joseph Grima ›

客服

消息

收藏

下载

最近