查看完整案例

收藏

下载

翻译

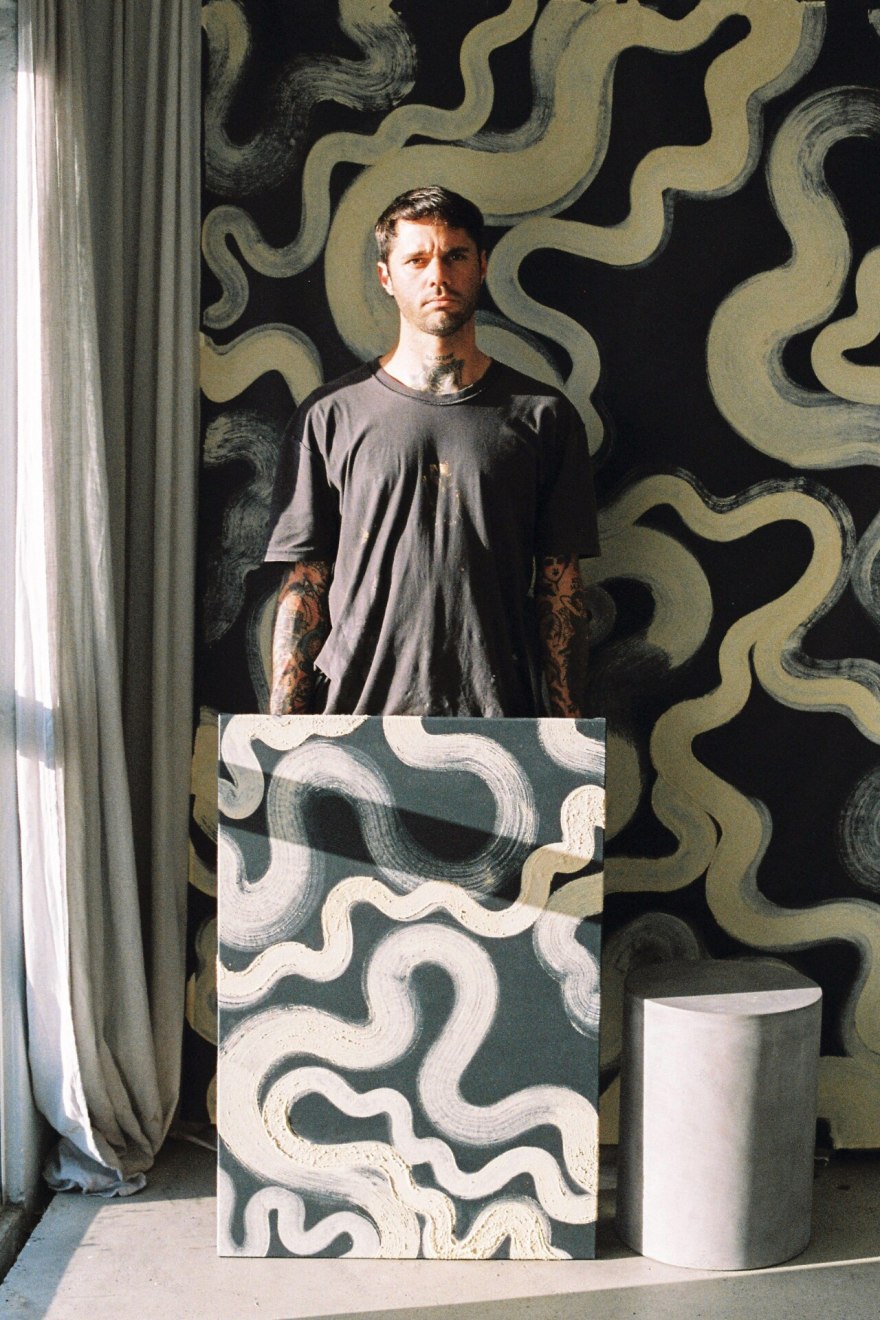

Artist Shal with his works, Jagun Balun — Home River. Image credit: Blake PaceThis story comes to you straight from the pages of ourMarch/April issueout now. For the full story, purchase a copy of the magazine or become aVogue VIPand take advantage of our digital and print subscription with exclusive offers and content.It seems like almost everyone has faced some sort of identity crisis since thepandemicbegan. To cope with the existential unease, many of us haveturned to art. And the practising creatives among us have been making it with gusto.Although these five artists come from disparate backgrounds and utilise different media, they are all creating work that grapples with identity, either individual or collective. It’s perhaps not surprising that the creative talents attracting the most attention are the ones trying to figure out who, exactly, we are now.Artist Shal. Image credit: Blake PaceShaun Daniel Allen (Shal)Sydney gallerist Edward Woodley says the opening night of Balun, Shaun Daniel Allen’s debut show, was extraordinary. “People sat on the floor and cried,” he recalls.The work the artist known as Shal has created since he took up painting in 2020 seems to depict water snaking across terrain. ‘Balun’ means ‘river’ in the language of the Yugambeh people, whose land lies near theGold Coastand Scenic Rim regions as well as Logan and Tweed Rivers.However, for some viewers, the work transcends this literal interpretation and provokes a deep emotional response. According to Shal, a Yugambeh/ Bundjalung man who did not grow up on Country, it is part of his ongoing search for belonging.“Identity is a weird thing for a lot of people like me,” he says. “I’m trying to figure out where I actually fit and who I actually am.”Already, Shal has a sure hand and a distinctive voice. Performing in punk bands and working as a tattooer have taught him not to second-guess himself. “In live music and tattooing, once you’re done, you’re done,” he says. “I’m trying to approach painting in the same way: expressing what I need to and then moving on.”His artistic practice and his relationship with Country are evolving in tandem. Using ochre sourced on trips home, he is in the midst of producing a substantial body of work for his next solo exhibition, to be held in Sydney later this year.Jagun Balun — Home River. Image credit: Blake PaceArtist Sam Gold. Image credit: Sia DuffSam GoldSam Gold seems to be everywhere right now. In the space of a few months, the South Australian ceramicist has been part of the Primavera 2021: Young Australia Artists exhibition at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art, signed with Hugo Michell Gallery and announced shows inAdelaideandCanberra.But Gold has not been rushing. The non-binary artist has, in fact, been developing their practice for almost a decade, first by training as a transpersonal art therapist, then by studying furniture design and contemporary art.Gold thought carefully before choosing ceramics as their long-term medium in 2018. “I love that it’s a non-judgemental mirror to yourself,” they explain. “When you’re centring on the wheel, whatever you bring that day shows up in the work. Each piece becomes a way of recording that moment and the energy of that day.” The artist’s sculptural ceramics defy easy description. Some viewers see coral while others make anatomical connections. “I’m putting these non-functional objects out there and allowing people to consider them in any way they see fit,” they explain.Whatever position you take on the work, it’s hard to deny Gold’s dexterity. Their pieces are elegant and precisely crafted. Perhaps, like a flower or a piece of coral, no further explanation is necessary.The body knows (2021) stoneware and liquid quartz sculpture by Sam Gold. Image credit: Sam RobertsArtist Mia Boe in front of a mural by an unknown artist. Image credit: Innerspace Contemporary ArtMia BoeShe’s young, progressive and keenly aware of her Aboriginal and Burmese heritage. Yet Brisbane-based painter Mia Boe is a happy disciple of the “old white men” who dominated 20th-century Australian art. “I’ve been so influenced by Russell Drysdale, Sidney Nolan and Albert Tucker,” she says. “My social perspective is very different from theirs, but I love their visual styles.”Boe’s interest in traditional figurative painters sets her apart from many of her peers. By referencing the Western canon in her works about colonial violence, she creates a sort of cognitive dissonance for viewers. “Dad moved here from Burma as a refugee when he was four, and Mum didn’t know she was Indigenous until she was 16, so my family has this common experience of growing up disconnected,” she says.In the two years since she started exhibiting, Boe’s practice has flourished. Residencies at the Museum of Brisbane and Brisbane’s Institute of Modern Art led to solo shows. Her latest show is with Blackartprojects at the Melbourne Art Fair in February.The new exhibition, which uses George Orwell’s writing on Burma as a jumping-off point, is Boe’s attempt at uncovering the pre-Australian history of her father’s family. She likens it to detective work. “I’m researching my parents’ cultures because I’m driven to learn more about myself,” she says. “I’m trying really hard to establish those connections.”The Colour Factory painting by Mia Boe.Artist Noah Spivak. Image credit: Sami HarperNoah SpivakWatching a photograph develop in a darkroom tray was a pivotal moment for mixed-media artist Noah Spivak. “It sparked something inside me, and ever since, I’ve been fascinated by chemicals and science-based work,” he says.After studying art in New York City and Vancouver, the Canadian native migrated to Melbourne with his boyfriend, an Australian whose visa expired. That was six years ago. “I didn’t think I would be in Australia for so long, but we just celebrated our 10-year anniversary,” Spivak says. “Melbourne has become home.”Since then, the artist has experimented with a range of media but has consistently employed chemicals to create work. A creative breakthrough came when he began making mirrors by applying silver nitrate to glass. Spivak’s mirrors straddle the line between art and design, inviting us first to view them and then to view ourselves within them. “Initially, you engage on a purely aesthetic level, but the more you look, the more you’re actually engaging with yourself,” he says.Melbourne has been good for the 29-year-old: since 2016, he has successfully mounted more than a dozen solo exhibitions and appeared in just as many group shows. Last year, he received the Emerging Artist Award from non-for-profit independent cultural hub Fortyfivedownstairs.He credits the city’s art scene for spurring him on. “Because there is so much creativity concentrated here, it’s highly competitive,” he says. “It drives you to be better and do better in the hope that you’ll be the one who rises to the top.”We Who Sit But Cannot Sit Still (waverley) (2021) artwork by Noah Spivak.Artist Ezz Monem. Image credit: This Is No FantasyEzz MonemLike many young Egyptians, photo-based artist Ezz Monem was hopeful that the Arab Spring would lead to secularism and true democracy in his native land. Instead, the 2011 uprising fuelled ongoing instability, followed by a retreat towards traditionalism.“My ex-partner and I are both trained engineers, so we decided to apply for skilled visas and move to Australia as a way of achieving a new life,” says Monem, who has been living in Melbourne for the past five years.Finding computer engineering and software developer jobs was easy, and the pair felt welcome in Australia. However, in the process of migrating, Monem had drifted away from photography, his true passion. Before relocating, he exhibited his work regularly in Cairo and Europe. “I realised that I couldn’t do both things any more,” he says. “So, I quit my job and enrolled in a Master of Contemporary Art at the Victorian College of Arts in 2018.”The gamble paid off. A newly energised Monem began making connections in the art world and soon caught the attention of contemporary gallery This Is No Fantasy, which represents Petrina Hicks, Vincent Namatjira and others. He is now part of that stable.To fund his education he works part-time jobs including being a delivery driver, which inspired a recent photo series. He documented his shifts using an old Diana camera then applied darkroom techniques. The result is an incisive study of the gig economy.Late last year, Monem was granted Australian citizenship. His upcoming exhibition at PHOTO 2022 International Festival of Photography will be his first as a dual national. “I’m still very connected to Egypt, and not being able to visit during the pandemic was difficult,” says the artist. “But now it feels different. I consider Egypt and Australia as two homes at the same time.”The Pyramids Postcards: Following the Policeman #2 (2018/2019) artwork by Ezz Monem. Image credit: Courtesy of the artistWant moreVogue Living? Sign up to theVogue Livingnewsletterfor your weekly dose of design news and interiors inspiration.

客服

消息

收藏

下载

最近