查看完整案例

收藏

下载

翻译

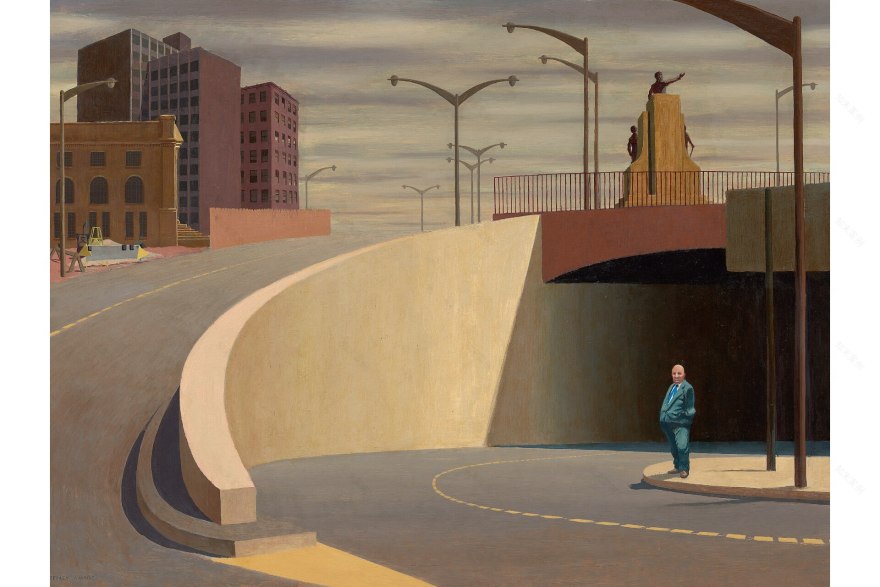

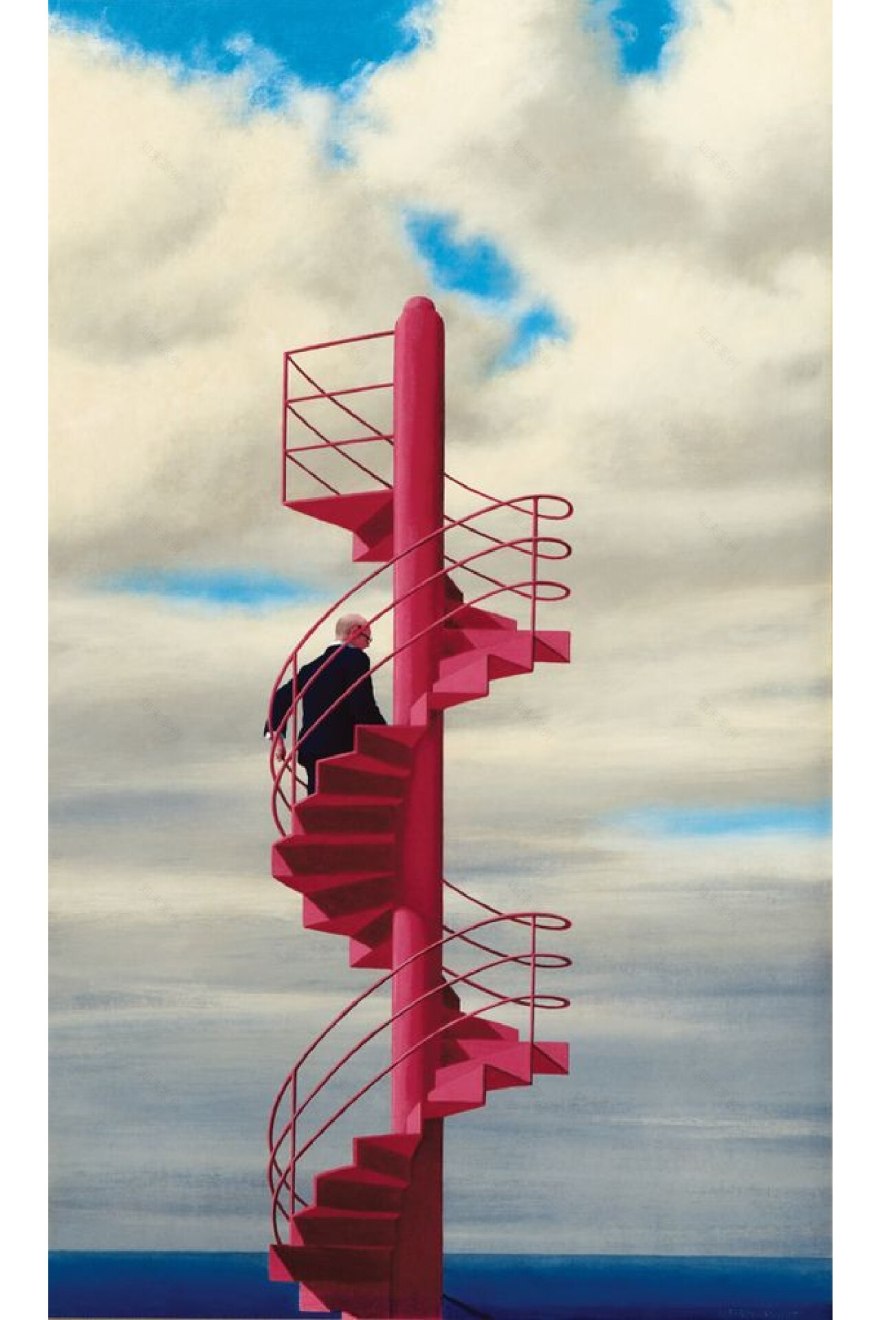

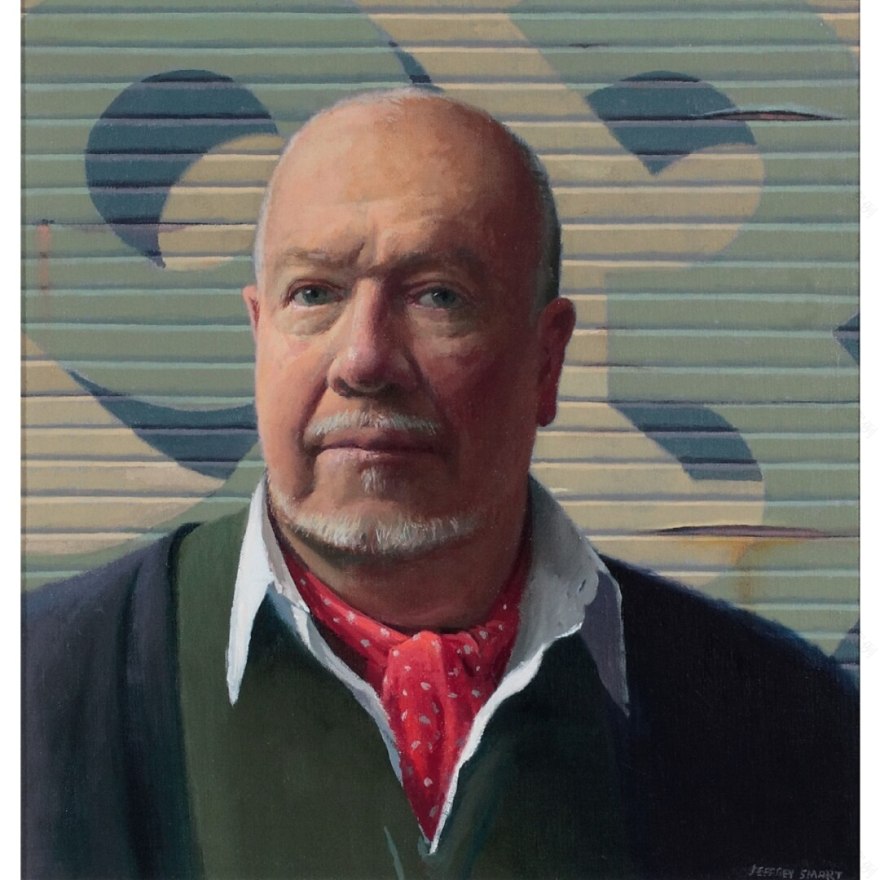

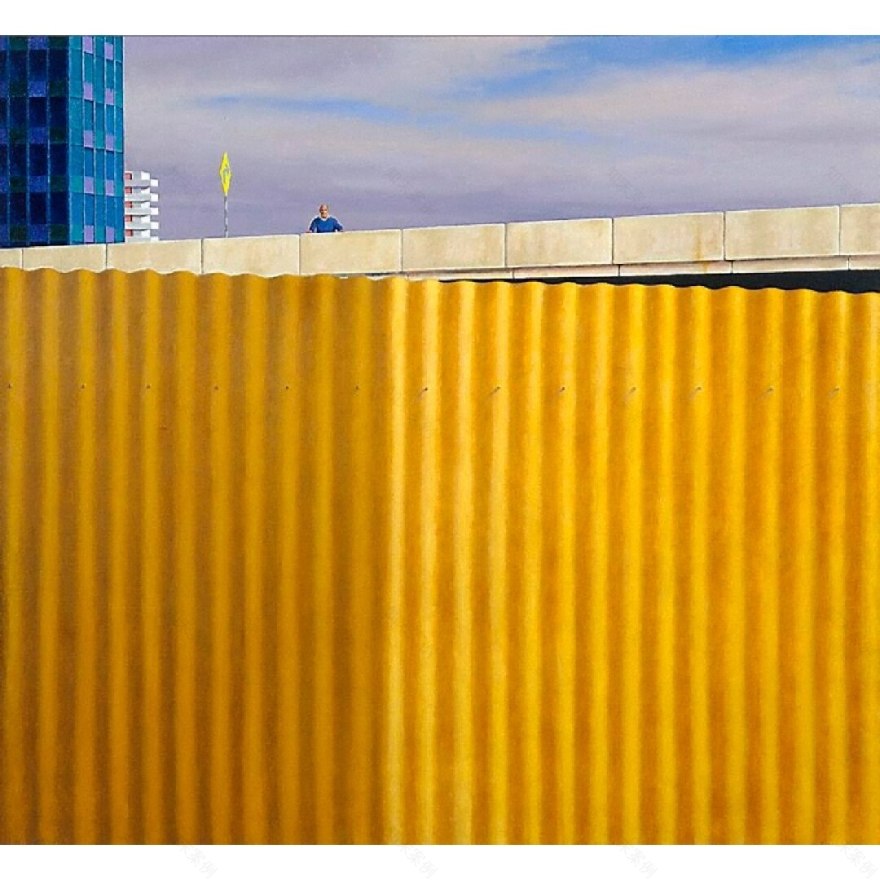

Above: Jeffrey Smart,Morning at Savona (1976)In Jeffrey Smart’s iconic artworkCahill Expressway, a lone figure watches us from a street corner. Around him are fixtures of Sydney’s urban landscape—a stretch of Macquarie Street lined with arboresque lampposts, construction debris on the Mitchell Library doorstep—but they seem as foreign as they do familiar. It is a painting often used to demonstrate the enduring relevance of Smart’s artistic vision. Here was the city frozen in time, and rebuilt by the artist with peculiar geometry.Smart, who was born in Adelaide in 1921, was an arts teacher before becoming a painter himself. He was influenced both byEuropean and Australian modernismand his love for the former sent him to Italy in the 1960s, where he lived in Tuscany until his death in 2013. But even after relocating to Europe, his urban vistas remained quintessentially Australian. Smart, unlike any other, was able to capture the man and the man-made within an Australian setting. In the landscape of our nation’s art, he towers.The figurative and the abstract, the intimate and uncanny, the Italian andAustralian—such are the dualities navigated by any curator tackling the breadth of Smart’s work for an exhibition. Often, there is the impulse to pick sides when unpacking his creative philosophy. But for the National Gallery of Australia’s (NGA) centenary retrospective of Smart’s groundbreaking seven-decade career, Rebecca Edwards and Deborah Hart, co-curators of the exhibition, wanted to explore all angles. “What if we let the exhibition be this imagined debate, taking different stances at the same time?” Edwards explains of their academic sparring. “What if one of us tried to claim Smart was only interested in figuration, and the other that he was interested in abstraction?”This curatorial approach allowed Edwards and Hart to embrace the complexities of Smart’s legacy as an artist in this milestone NGA retrospective. A staggering 130 works are arranged in broad chronology, beginning with his formative years in Adelaide. But the exhibition’s defining structure lies in its chapters; themes of portraiture, surveillance and self-reference that create a conversation between several works separated by time, as well as a selection of Smart’s lesser-known pieces.“We haven’t tried to bring together, every famous work by Smart,” says Hart. “That wouldn’t have been adventurous.” With the distance of almost a decade since his passing came the opportunity to view Smart from a critical vantage point: “We can reassess the impact of his art in full,” shares Edwards, “how it fits into context, or rubs up against it.” For the curators, Smart’s creative output is both at one with, and separate from, our modern era. His birth coincided with upheaval after World War I, while his adulthood set him on a parallel course with the Depression and World War II.“Things were coming apart,” says Hart. “He tried to rebuild these broken images, to distil his environment.” It seemed radical to paint stillness in the midst of modernity’s frenetic rhythm, to find beauty in the urban and mundane, and yet that is exactly what Smart does. Service stations, corrugated iron, neon signage—nothing was too ordinary. “Everything has a place, like a haiku,” says Hart. Time, in the eye of Smart’s work, is also circular. “His images of isolation seemed surreal two years ago,” says Edwards, “but now, they’ve become eerily prescient. How many of us have seen the same scenes in lockdown—empty streets, barren of people?”This, Hart believes, is the power of Smart’s work: that these paintings invite stories, rather than telling them. “He constructs these theatrical sets, and frees up possibilities for imagining,” sums up Hart. “You see the same props and actors, too,” elaborates Edwards, referring to Smart’s recurring nonnas and flâneurs, “but there’s never a plot. The viewer writes the script.”The radicalism of Smart’s work comes from this elusiveness, and if his paintings are like theatre, they are plays without an ending. The curtains don’t close, but stay open and alert. The drama lives on.Below, ten works not to miss from the exhibition, on now at the National Gallery of Australia.Sign up to theVogue Living newsletterJeffrey Smart,Cahill Expressway(1962)Jeffrey Smart,Jacob Descending(1978-79)Jeffrey Smart,ThePlastic Tube(1980)Jeffrey Smart,Self-portrait(1993)Jeffrey Smart,Service Station Calabria(1977)Jeffrey Smart,Corrugated Giaconda(1976)Jeffrey Smart,Autobahn in the Blcak Forest II(1979-80)Jeffrey Smart,TheLighthouse, Fiumicino(1968-69)Jeffrey Smart,Portrait of Clive James(1991-92)Jeffrey Smart,Labyrinth(2011)This article first appeared inVogueAustralia’s January 2022 issue.Want moreVogue Living?Sign up to theVogue Livingnewsletterfor your weekly dose of design news and interiors inspiration.Subscribe to Vogue Living and you will become a member of our Vogue VIP subscriber-only loyalty program and be rewarded with exclusive event invitations, special insider access, must-have product offers, gifts from our luxury partners and so much more.Subscribe today.

客服

消息

收藏

下载

最近