查看完整案例

收藏

下载

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice

Project Data

Full Team

Year

2018

Status

Completed

Size

30,139 sq ft

Location

Montgomery, Alabama, United States

Collaborators

Arborguard, Dana King, Delta Fountains, Doster Construction, Hank Willis Thomas, Howe Engineers, Kwame Akoto-Bamfo, Lam Partners, Mazzetti, NOUS Engineering, Pilgreen Engineering, Robert Schwartz and Associates, Small Stuff, Steiner Studio

Focus areas

Civic Spaces & Cultural Centers, Memorials & Monuments, Parks & Public Spaces

Services

Architecture, Exhibits & Interpretation, Film & Media, Landscape Architecture

Project Team

Alicia Olushola Ajayi, Caroline Alsup, Sierra Bainbridge, Justin Brown, Chieh Chih Chiang, Ola Dosekun, Jessi Flynn, Emily Goldenberg, Whitney Hansley, Kordae Henry, Michael Murphy, Martin Pavlinic, Alan Ricks, Tom Ryan, Adam Saltzman

Full Team

Project Team

Alicia Olushola Ajayi, Caroline Alsup, Sierra Bainbridge, Justin Brown, Chieh Chih Chiang, Ola Dosekun, Jessi Flynn, Emily Goldenberg, Whitney Hansley, Kordae Henry, Michael Murphy, Martin Pavlinic, Alan Ricks, Tom Ryan, Adam Saltzman

Alan Ricks

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice is the first national memorial to lynched Black Americans, giving form to their silenced history.

Designed in partnership with Bryan Stevenson and the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) in Montgomery, Alabama, the six-acre site provides space for truth-telling, hope, healing, and reconciliation. The memorial is part of the Legacy Sites, which also include the Legacy Museum and the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park.

Iwan Baan

In one of the most comprehensive investigations to date, the Equal Justice Initiative documented more than 4,000 raced-based lynchings in twelve Southern states between Reconstruction (1870) and World War II. Their work recognized the need for marking the legacy that originated with these gruesome acts, one that could hold a space for recovery and reconciliation.

National Memorial for Peace and Justice, AL

Alan Ricks

The United States has done very little to recognize the lasting societal trauma perpetuated by the history of slavery and its aftermath. Decades of racial terror, lynching, segregation, and a mass migration from the South precipitated an environment of extreme fear, one where racial subordination and segregation were brutally enforced.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice marks the beginning of amends for these atrocities, filling a gap in a city that actively commemorates the Confederacy through historical monuments with comparatively few markers for the Civil Rights Movement.

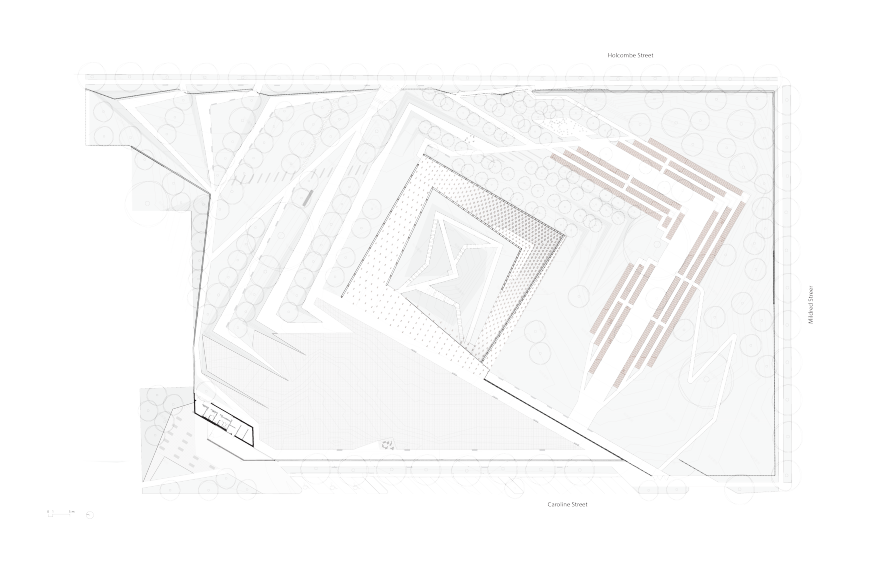

The memorial’s site reutilizes a formerly vacant lot once used for public housing and single-family homes, which were demolished in the early 2010’s after these structures were left vacant for several years. Project construction reshaped this landscape, removing the leftover asphalt, concrete, and other non-permeable materials.

The memorial sits atop a central hill whose elevation allows for views of downtown Montgomery. The main structure houses 810 suspended Corten steel monuments—one for each US county where racial terror lynchings took place—engraved with victims’ names. Visitors enter the memorial’s central structure via an inner walkway that lowers in elevation and changes the viewer’s relationship to the monuments suspended above at a constant height.

Duplicates of the monuments lie in the memory bank outside the main structure. Counties are invited to retrieve their monument, and in doing so, acknowledge a violent chapter of their history. Through this retrieval, the memorial becomes a means rather than an end, devoted to a process of truth-telling, reconciliation, and healing.

Alan Ricks

Alan Ricks

"To my mind, it is the single greatest work of American architecture of the 21st century... Here, too, abstraction, repetition, typography and procession are mobilized to produce an experience that is at once revelatory and heartbreaking... It is one thing to read statistics; the memorial’s strength resides in its ability to translate those numbers into a devastating physical experience."

Mark Lamster, The Dallas Morning News

Alan Karchmer

Iwan Baan

Iwan Baan

All planting elements are native to the area. Meadow landscaping strategies used these plantings to restore regional biodiversity to a disturbed urban lot. Tree selections similarly replaced the monocultural environments, with the exception of a grove of longleaf pine trees beside the memorial, which intentionally refers to the tremendous loss of free labor and refusal of plantation owners to pay fair wages to those who once were enslaved. Across the south, logging replaced cotton fields and can still be understood today as markers of the communities torn apart by terror lynchings and the the Great Migration that ensued.

Alan Karchmer

Dallas Morning News: "The single greatest work of 21st century American architecture will break your heart."

Royal Institute of British Architects: 2021 International Awards for Excellence

Boston Society of Architect: 2019 Honor Awards for Design Excellence

The New York Times: "A Memorial to the Lingering Horror of Lynching"

ArchDaily: "Social Impact: Architecture Building Space for Empathy"

客服

消息

收藏

下载

最近