查看完整案例

收藏

下载

翻译

Title: Mapplethorpe+Munch

Posted In: Painting , Photography , Exhibition

Duration: 06 February 2016 to 29 May 2016

Venue: The Munch Museet

Opening Hours: Every Day 10.00 - 16.00

Location: Tøyengata 53 0578 Oslo Norway

Telephone: (+47) 23 49 35 00

Email: [email protected]

Visit Website: munchmuseet.no

Mapplethorpe+Munch brings together for the first time works by two great artists, Robert Mapplethorpe and Edvard Munch. Organised by the Munch Museum in Oslo as part of +Munch, an ongoing exhibition series juxtaposing Munch’s art with that of six other significant artists, the exhibition reveals surprising similarities and parallels between the two men in both subject matter and disposition and provides new perspectives on their art.

Mapplethorpe + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016). Installation view. Photo by Vegard Kleven.

The exhibition, presenting 141 works from Mapplethorpe and 95 from Munch, is divided in several thematic sections—self-portraits, the female nude, faces & flowers and sexuality—demonstrating how both artists extensively used two traditional genres, nudes and portraits to explore common themes such as sexual liberation, gender, identity and religious aspiration. Both being members of a bohemian subculture of artists, and emerging during a time of cultural change and upheaval (Munch in the 1880s and Mapplethorpe the 1970s), the pairing of their work also draws attention to their shared defiance of the establishment and their attempt to stretch the boundaries of their art.

Mapplethorpe + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016). Installation view. Photo by Vegard Kleven.

Self-portraits The exhibition begins with Mapplethorpe’s black and white self-portrait from 1988, taken only months before he died from an AIDS-related illness, which is presented side-by-side with Munch’s “Self-Portrait with Skeleton Arm”, a monochrome lithograph from 1895; the two works share a similar visual composition and an acute awareness of mortality. Both artists were prolific in producing self-portraits throughout their careers. For Mapplethorpe, personality was considered “serial” as the critic Peter Conrad asserts, and in his self-portraits he often therefore takes different roles, depicting himself dressed as a woman, a hoodlum or a terrorist. Munch’s self-portraits also serially depict the artist in various stages in his life, from his arrogant and self-assured younger self, to a drunken, catatonic middle age self, all the way to the sick, ageing self of his final years.

Mapplethorpe + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016). Installation view. Photo by Vegard Kleven.

Mapplethorpe + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016). Installation view. Photo by Vegard Kleven.

Hung next to each other, Munch’s “Self-portrait in Hell” (1903) and Mapplethorpe’s self-portrait with devil horns (1985) share the same eerie self-awareness, the former capturing the artist’s sense of suffering and misery whereas the latter captures the artist’s darker side. In the same section, Munch’s series of photographic self-portraits from the early 20th century viewed alongside Mapplethorpe’s Polaroids of himself exploring his sexuality —this is in fact the only time they use the same medium— reveal their willingness to expose themselves with brutal honesty.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016). Installation view. Photo by Vegard Kleven.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016). Installation view. Photo by Vegard Kleven.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016). Installation view. Photo by Vegard Kleven.

Mapplethorpe + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016). Installation view. Photo by Vegard Kleven.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016). Installation view. Photo by Vegard Kleven.

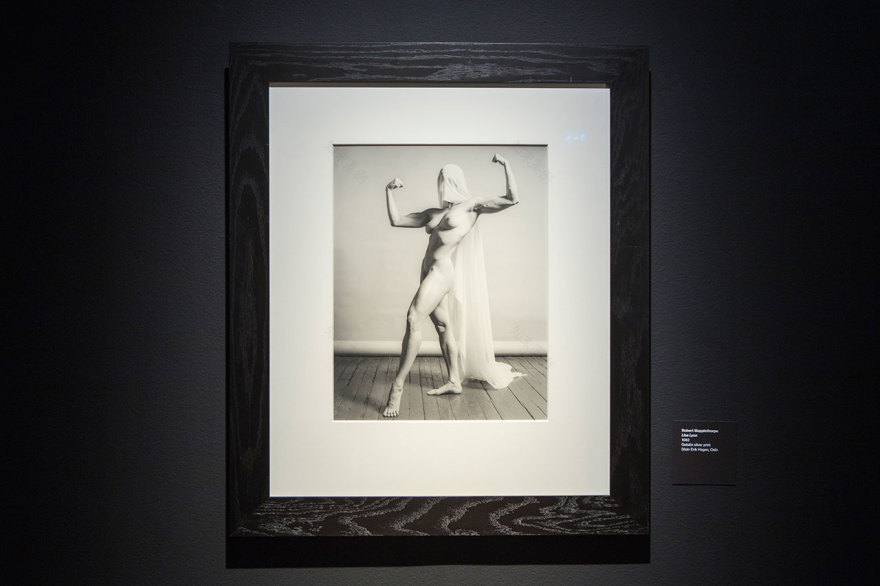

Nudes In another parallel arc in their lives, not only did both Mapplethorpe and Munch work extensively with female nudes, they also each had a muse who inspired them to produce series of work. For Munch it was Annie Fjeldbu who sat for him for five years around 1920 and can be viewed in several full-length poses along Mapplethorpe's model, Lisa Lyon, a pioneer in female body building, whom he photographed during three years in the early 80s in numerous stereotype-breaking roles. Parallels can also be found in the two artists’ exploration of the male nude: in Munch’s “Standing Naked African” (1916) and Mapplethorpe’s images of naked black men, there is a pronounced sculptural quality, a glowing physicality elevated to the Platonic ideal of human form.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016). Installation view. Photo by Ove Kvavik. Courtesy the Munch Museum.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016). Installation view. Photo by Ove Kvavik. Courtesy the Munch Museum.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016). Installation view. Photo by Ove Kvavik. Courtesy the Munch Museum.

Portraits Both artists excelled at creating portraits, most notably of famous friends and acquaintances, many of them on commission. The objective behind Mapplethorpe’s portraiture was to get at the plurality and fluidity of a person’s identity, something that can be sensed in Munch’s work too. His portrait of Dagny Juel Przybyszewska (1893)—a Norwegian writer, famous for her liaisons with various prominent artists, and for the dramatic circumstances of her death—displayed next to Mapplethorpe’s photograph of Grace Jones (1975), although quite different in aesthetics, style and size, the one a coloured oil painting, the other a black and white photograph, both carry a distinct emotional weight with the two women exuding both vulnerability and self-assurance.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016). Installation view. Photo by Ove Kvavik. Courtesy the Munch Museum.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016). Installation view. Photo by Ove Kvavik. Courtesy the Munch Museum.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016). Installation view. Photo by Ove Kvavik. Courtesy the Munch Museum.

Coming full circle the exhibition concludes with Munch’ self-portrait as a naked, ageing man and Mapplethorpe’s final self-portrait before his death showing just his eyes, successfully threading together the two artists’ oeuvre and lives in a coherent narrative of self-exploration. It is also a reminder that art, with its relentless exploration of the human condition, is timeless and universal.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016). Installation view. Photo by Ove Kvavik. Courtesy the Munch Museum.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016). Installation view. Photo by Ove Kvavik. Courtesy the Munch Museum.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016). Installation view. Photo by Ove Kvavik. Courtesy the Munch Museum.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016). Installation view. Photo by Vegard Kleven.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016). Installation view. Photo by Vegard Kleven.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016). Installation view. Photo by Vegard Kleven.

Mapplethorp + Munch exhibition at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2016). Installation view. Photo by Ove Kvavik. Courtesy the Munch Museum.

客服

消息

收藏

下载

最近