查看完整案例

收藏

下载

翻译

In our ongoing profile series, we go home, from home, with artists to hear about what they’re making, what’s making them tick, and the moments that made them. Here, we speak to pioneering American artist Charles Gaines about how grids, formulas and systems can drive conceptualism

Charles Gaines in his Los Angeles studio, 2020 © Charles Gaines Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photography: Fredrik Nilsen

Over the last 50 years, American conceptual artist Charles Gaines has generated a practice dense with concept, yet devoid of self-expression. Through the power of the grid, mathematics, and rules-based processes, he interrogates tensions between indeterminacy and rationality; subjectivity and objectivity; race and representation.

This year will be a busy one for the artist. His first solo show in the UK is open now at Hauser & Wirth London, until May, presenting new phases of his acclaimed Numbers and Trees and Numbers and Faces series. In February, Dia Beacon in New York will host a survey of Gaines’ early grid experiments and recent investigations into the representation and deconstruction of identity. A show at SFMoMA in spring 2021 will include the next iteration of his acclaimed Manifestos series, in which revolutionary manifestos are translated from text to musical notation.

Alongside his practice, Gaines is a revered educator at the California Institute of the Arts, where he recently established the Charles Gaines Fellowship to support Black Students in the MFA Art programme.

We caught up with the artist, via Zoom, from his new LA studio to discuss forging a path with no mentors, fusing music and art, and confronting the myths of modernism.

Charles Gaines in his Los Angeles studio, 2020 © Charles Gaines. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photography: Fredrik Nilsen

W*: Where are you as we speak?

Charles Gaines: In my new studio, an 11,000 sq ft warehouse designed by architect Peter Tolkin. It has a saw-tooth roof design which is common in LA industrial architecture, where the vertical side of the sawtooth is glass. It faces north, so the light in the building is just unbelievably beautiful. We have a 2000 sq ft gallery where I’m able to hang work in production. When Covid is over, I want to use the gallery for public programming.

I never thought I would have a studio like this. I have conflicted feelings because it’s really beautiful, but way beyond anything I or anybody needs. But after 50 years of making art, I’m just going to spend the next few years not beating myself over the head, and just enjoy it.

W*: Can you tell us about the piano behind you? Is it modified for your artistic purposes?

CG: It’s an electric piano. You probably know about the Manifestos series, where I write music translated from texts – I’m in the middle of a new one. My use of music is very conventional; what’s different is the way compositions are written. I depend on ordinary Western instruments and use the diatonic scale. I create a set of rules which translate letters into notes, so that part is different. It sounds very much like something produced by regular compositional rules but is produced by a system. It’s that paradox that I want to exploit.

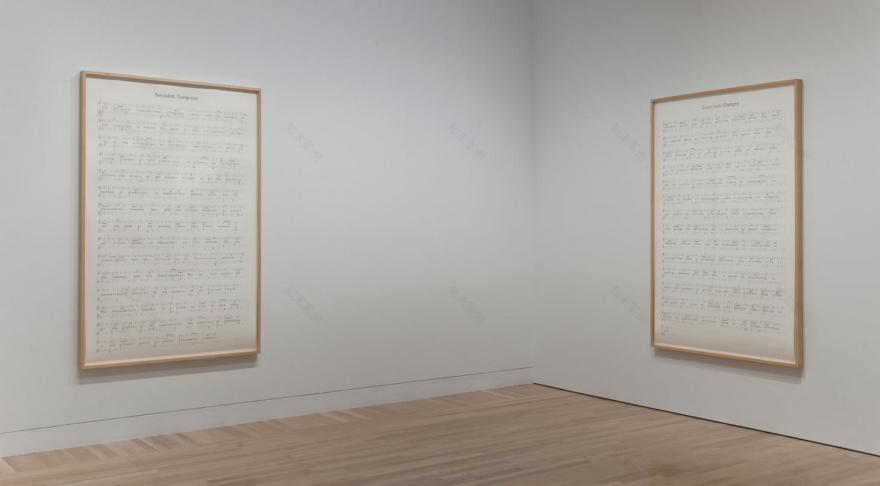

Charles Gaines, Manifestos, 2008, Installation view, ’All of this and nothing’, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles 2011. © Charles Gaines. Courtesy the artist and Hammer Museum. Photography: Brian Forrest

W*: When did your interest in music start?

CG: I was trained as a musician. I went to art school, but at the same time, I studied instruments. Then I became a drummer and played professionally most of my younger years until I stopped in my thirties. But I still play and I’ve gone back to playing a lot. I learnt music theory by studying instruments, but it wasn’t until seven or eight years ago that any of that experience entered my studio practice; they were always separate things.

W*: So when you were learning music theory, you weren’t thinking about how those sets of rules might translate visually, or how the disciplines could interlink?

CG: When I was in high school, there weren’t any models for where the boundaries between music and art had been dissolved. Eight years ago I ran into Terry Adkins, who had also been trained as a musician and had an art practice that seemingly included his music experience – that was the first time I’d seen that.

One of the consequences of the avant-garde was the dissolution of boundaries between various practices and strategies – a kind of montage or collage of practices. Music was treated like sound, like a sculptural material, but I wasn’t interested in that. What Terry was doing helped me come up with an idea where visual art and sound couldn’t be separated.

W*: Much of your work appears in intricate grid-like formations. What has consistently drawn you to this format?

CG: The grid works are simple arithmetic systems using numbers to assign locations on a grid. If you ‘grid’ an object, then you’ve turned an object into a structure, but you haven’t undermined the object, the object is not lost. I am not looking for pure abstraction.

As sentient beings, we don’t just see patterns, we see objects in the way our brains are structured, but it does reveal that there is a process of converting these patterns into objects, and that process is language. The language we speak obeys the same laws of physics as any other perceptual object.

Charles Gaines, Manifestos, 2008, Installation view, ’All of this and nothing’, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles 2011. © Charles Gaines. Courtesy the artist and Hammer Museum. Photography: Brian Forrest

W*: So for example in your Manifestos series, you translate texts and language into sound. How do you approach this?

CG: The structure of language is highly mathematical. It’s syntactics; a pure relationship of sounds before they become words. That’s when music stepped in, because if I work with music as sound, I can make a relationship between music and language.

It becomes significant when the art built from that place is different from more conventional strategies of art-making, those based on self-expression and the imagination. And I’m not using either when building a work of art.

W*: We’re interested in this idea of removing subjectivity from the process of producing art. Wouldn’t the conception of an idea require creativity?

CG: There’s a general notion that modernism has abused the idea of creativity and expression. It perpetuates certain myths, like the belief that art comes from one’s subjectivity; that there is this transcendent place called the ‘subject’. If I am a modernist and want to advance the ideas of modernism, I am producing an ideology, not a truth. But it’s a particularly cynical ideology because it removes the mechanism of criticism: if I express something, no one can say what I’ve done is not an expression.

People often ask, ‘How can invention or creativity can exist within this framework?’ There’s a certain point within a piece where the set of rules can lead you to the idea of another set of rules, and that’s an invention.

W*: When did these interests in structures and rules-based systems begin?

CG: When I went to graduate school. I realised that the whole activity was dominated by the language of self-expression. I watched my peers in the studio and fancied myself as an anthropologist studying the behaviour of artists. There’s this notion that it all happens in the present, that it’s spontaneous and intuitive. I thought, ‘Yeah, I can behave like that.’ So I would just stare at the canvas until an idea came, and made an object that people actually found interesting. But it seemed stupid to me. I could have done anything!

It was either quit and go to law school, or find a way of making art that was meaningful to me. I discovered there were other ways of making art than the Western way of working from the subjective unconscious. I found Hanne Darboven’s work and was fascinated by her gridlike structures and the interesting problem of finding differences in repetition.

That’s how my first series, Regression (1973-1974) happened, working with images like trees. For the first time in my life, I had fun making a work of art, even though people looked at the repetitive nature of it thinking ‘How in the world could he be having fun doing this?’

Charles Gaines, Numbers and Trees: London, Series 1, Tree #6, Fetter Lane, 2020. © Charles Gaines. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photography: Fredrik Nilsen

W*: How in control do you feel during the process?

CG: I have no control. People think I lie when I say I’ve given up control because they think that when you make a choice, that’s an expression. People make choices all the time and they’re not making art. Everything I do is a result of what is given to me; I don’t make aesthetic decisions. In the trees, you see all these pretty colours and people think I’m operating with the poetics of colour, but It’s quite mechanical. A lot of my interest is to show that aesthetics can still exist and that you can fully involve yourself in them, by virtue of the machine.

W*: You’re presenting the latest instalment in your Numbers and Trees series at Hauser & Wirth soon. What draws you to trees, and how do you create numbered sequences from them?

CG: When I knew I was going to have the show, one of the directors at Hauser & Wirth, Henry Allsopp, insisted that I go around England with him and look at British oaks. I wasn’t going to do a tree piece, but Henry was right, something was going on with these trees that I hadn’t dealt with in the other work. In my tree work, there are two strategies: one where I plot the shape of trees over a photograph of a tree, and another where I plot the shape of trees over a painting of a tree. With this one, I decided to use an exploded photograph of the tree.

The [British oaks] are big, old and craggy, but they still maintain this scale and symmetry. If I tried to do this with some [trees] in the American West, like redwoods, it would be a different experience.

Charles Gaines, Numbers and Trees: London, Series 1, Tree #6, Fetter Lane, 2020. © Charles Gaines. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photography: Fredrik Nilsen

W*: You’ll also be exhibiting new work from the Numbers and Faces series you began in the 1970s. Can you talk us through the origins of the series, and your latest chapter?

CG: The faces series I did in the late 1970s, up to the early 1980s, were drawings. I didn’t make any more until a show I had at Paula Cooper Gallery a few years ago called ‘Identity Politics’. I did a grid drawing of the face, plotted that on Plexiglas and layered faces of important figures that dealt with identity, like Aristotle.

This series is a continuation, but the subject is race and ethnicity. I invited people [via an open call] who self-identify as multi-racial or multi-ethnic to volunteer to be photographed, then I plotted their faces. When you use a face, there are always questions about the person. I wanted to diminish the significance of these questions, but the questions were irrepressible anyway.

I hope people will read an analogy where the characteristics of race become more and more diffused. When you have a biracial person, that fusion creates a politically volatile figure that most cultures try to dismiss as one or the other. A person who is white and African, for a number of social and political reasons, is called Black, but they are just as white as they are Black. I was hoping that this notion of race as construction would be amplified through the merging of multiple faces.

Above: Charles Gaines, Numbers and Faces: Multi-Racial/Ethnic Combinations Series 1: Face #7, Eduardo Soriano-Hewitt (Black/Filipino), 2020. Below: detail. © Charles Gaines. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photography: Fredrik Nilsen

W*: Throughout your career, which artists, writers or musicians have had the biggest impact on you?

CG: I don’t have an artist that I think was instrumental. Hanne Darboven is hugely important to me, but my work is not like hers, it’s not even made for the same reasons. It’s one thing to like someone’s work, it’s another where you feel there’s a relationship.

I credit Sol LeWitt with getting my career started. He recommended me for inclusion in a major show, which resulted in me getting picked up by Castelli Gallery. So he was huge, but he wasn’t an influence.

I have a real affinity with the work of Steve Reich and a little bit of Philip Glass in terms of the repetition. John Cage was somebody I had a philosophical commitment to because his notion of indeterminacy plays extremely well in music systems. The idea of making a work of art that wasn’t a product of subjectivity came from him. §

Above: Charles Gaines, Numbers and Faces: Multi-Racial/Ethnic Combinations Series 1: Face #11, Martina Crouch (Nigerian Igbo Tribe/White), 2020. Below: detail. © Charles Gaines. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photography: Fredrik Nilsen

In a video produced by Hauser & Wirth, artist Charles Gaines previews his upcoming London exhibition, ’Multiples of Nature, Trees and Faces’. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

客服

消息

收藏

下载

最近