查看完整案例

收藏

下载

《新门神》(表演者:陈宇飞)

The New Door God (Performer: Chen Yufei)

© Yolanda vom Hagen

《花·石·水》(表演者:张诺然)

Flower, Stone, and Water (Performer: Zhang Nuolan)

© Yolanda vom Hagen

《预·见》(表演者:陈欣茹)

Foresee(Performer: Chen Xinru)

©Yolanda vom Hagen

在加入"盘上海"驻村项目的团队后,我不禁思考:作为建筑师我该如何来介入这场演出。参加活动之前我原本设想设计一个竹或木的装置缠绕着这个祠堂的构件,但是进入歙县郑村“郑氏宗祠”后,这个尺度巨大,颇具韵律感,充满着神圣性的空间带给我的震憾,让我感觉到空降一个看似酷炫的“当代”装置似乎是多余的。

After joining the residency organised by Pan Shanghai, I considered how I could intervene in the project as an architect. I originally intended to design a bamboo or wood installation wrapping around the components of the site-building, the Zheng Clan Ancestral Temple in Zheng Village, She County, Anhui Province, China. However, entering the temple, I was stunned tremendously by its huge, rhythmic, and sacred space, realising that adding a "distinctive contemporary" installation might be redundant.

郑氏宗祠入口牌坊

The Entry Gateway of the Zheng Clan Ancestral Temple

© 韩心宇

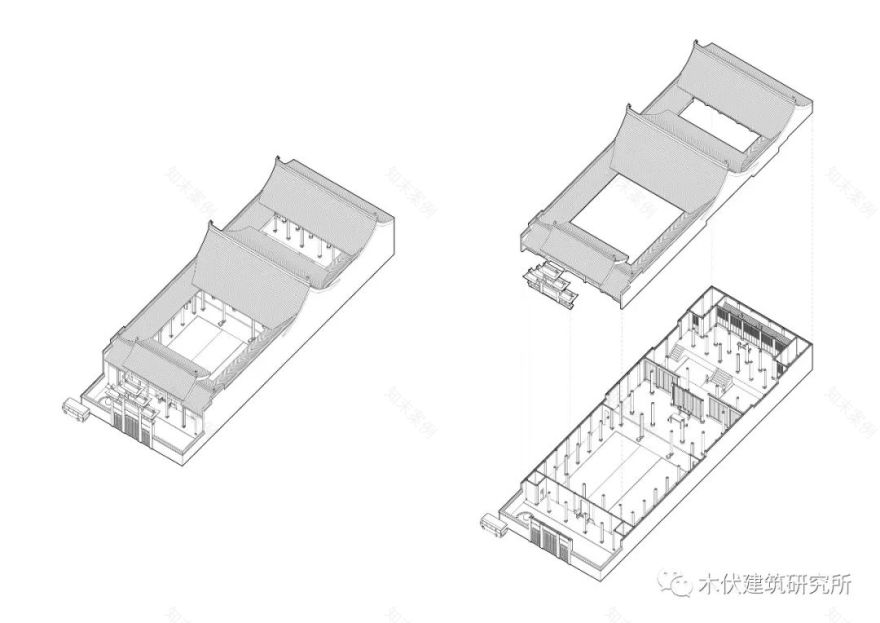

郑氏宗祠空间

布局

The Spatial Layout of the Zheng Clan Ancestral Temple

©木伏建筑研究所

主庭院

The Main Courtyard

©Yolanda vom Hagen

初次进入这个空间,我有两点感受。第一,在这样一个对祖先敬拜的空间中,表演应是娱人的也是娱神的。在中国大量的祠堂建筑中,戏台置于入口,朝向正厅(即祖先的方向)。我自己在福建曾有一次经历,在一个街头的庙会,我站在了观众席的最后观看,却被保安叫开,原因是我无意间挡住了我身后一个并不起眼的神龛。郑氏宗祠虽看不到戏台的痕迹,但我想这个大的格局逻辑应是一致的。第二,我看到同行的舞者在祠堂中的庭院即兴起舞,虽然舞者的表演让我叹服,我也完全相信他们不借助实体就能完成出色的舞蹈。但是对我而言,祠堂的庭院还是过于空旷,在其中设置一个特定高度的舞台支点,能化解这种视觉体验的瑕疵,并带给舞蹈更多的可能性。

Seeing this space for the first time, I had two judgements. First, our performance should entertain not only the villagers but also the ancestors in such a worship space. It is at the entrance of many ancestral temples in China that the stages are placed, facing the main hall, the direction of the ancestors. I once had a relevant experience in Fujian province. At a street temple fair, I stood at the rear of the spectators and watched the performance, but was actually asked to move aside by a security guard. It was because I accidentally blocked a humble shrine behind me. As for this project, I believed that the Zheng Clan Ancestral Temple, although without a stage, also follows this spectating rule. Second, a stage fulcrum in the main courtyard should be necessary. I was impressed by my fellows’ improvising dances in the main courtyard. Although I believed that they could accomplish excellent dances only with their own bodies, I thought that an installation of a certain height placed in the centre of the courtyard could bring about more possibilities for the dances and meanwhile improve the visual quality of the too hollow courtyard.

即兴舞蹈 Impromptu Dance©Yolanda vom Hagen

在第一天和第二天与村民的交流走访中,我原本试图挖掘出村民记忆中对每一处祠堂空间的使用记忆。但是令人惊诧的是,他们对于祠堂空间的认知甚为模糊,甚至是接近空白。解放后这个祠堂就再未举行过祭祀活动,在文革期间它被作为粮站使用。现在村中的老人在当时都还是孩子,基本不被允许进入祠堂内部的工作区,只能在祠堂外玩耍。近些年,出于对这处全国重点文物保护单位的保护,祠堂的大门一直处于关闭状态。由于郑村现存古建筑相对不密集,相比较周边的一些其他村落,缺少旅游产业的刺激,祠堂也便没有了开门的动力。

On the first and second days of the residency, I tried to dig out the villagers’ memories about the ancestral temple’s spaces via interviews. However, to my surprise, the villagers’ cognitions of the spaces were rather vague because they had rarely been in the building. The reason was: The temple stopped holding sacrificial activities after 1949 when the People’s Republic of China was established, and it was used as a barn during the Cultural Revolution; the elderly villagers today, being kids decades ago, were not allowed to enter the barn, a working area, and they were only permitted to play outside the building. In recent years, the building, as a national heritage site, has been kept closed all the time for conservative reasons. Compared with some other nearby villages, the number of existing ancient buildings in Zheng Village were relatively small. As a result, without the tourist stimulation, there was no incentive to open the ancestral temple.

说鳖会

Story

Circle

©Yolanda vom Hagen

第二次进入祠堂,我在思考:如果不做复杂的空间构筑物搭建,还有什么是可以在表演中运用的空间语言?我注意到正厅明间、次间对应的背板其实是装有转轴的,这意味着从建筑设计思维上,这些背板是会被安排开启的,称为屏门。想到自己本科时所在的剧社曾表演过一部话剧,当剧情进入高潮时,剧场排练厅和舞台之前的隔墙续续升起,两个空间被打通了,观众所见舞台的进深瞬间被拉大,玻璃幕墙外星星点点的灯火透入观众厅。我想:对于这个祠堂空间,如果屏门瞬间打开,也会有类似的效果。这样,祖先牌位所在的第二进院落和大众所在的第一进院落就能沟通起来。从礼制角度,这些屏门能否被打开,我与几位学建筑史的同门进行了讨论。虽然没有得到确定的结论,但是我推想:既然中间三间的背板被设计成屏门的形式,而两尽间却是固定的,或许从祭祀仪轨的角度来说,在仪式的特定阶段,这些屏门会被开启来表达祖先和后代间的某种相互的姿态和强化两者间的联系。祠堂一共包括四道门,牌坊下的栅栏门、门屋的正门、正厅的屏门、神龛的龛门。后三者属于原始建筑就存在的部分,我希望将它们纳入演出。我和伙伴们用了很大了力气推开了正厅的左右次间早已卡死的两处屏门,让它们能够活动。门的开启成为了演出中的动态,并导致了空间的改变,于是,门和空间成为了演员。

Entering the ancestral temple for the second time, I conceived the performative spatial strategy if a complicated structure were not to be built. The answer was using the motion of gates. There are four groups of gates in the ancestral temple: the fence gate under the archway, the main gate at the entry hall, the screen-gates at the main hall, and the niche gates of the shrine. I hoped to involve them in the performance. The backboards of the primary room and the secondary rooms of the main hall were noticed equipped with spindles, which meant that the backboards, academically called Pingmen (screen-gates), could be opened according to the architectural design concept. An experience of a drama society in my undergraduate school inspired me. When the play reached its climax, the partition between the rehearsal hall and the front stage of the theatre gently rose, connecting the two spaces. Thus the spectators’ view was instantly deepened, and they were amazed by the twinkling lights from outside going through the glass curtain wall around the rehearsal hall. As for the Zheng Clan Ancestral Temple, a similar effect could occur if the screen-gates could open instantly. In this way, the inner courtyard and shrine, where the ancestral tablets sit, could be connected with the main courtyard, which the spectators were occupying. But whether these screen-gates were allowed to be opened from the perspective of etiquette? I discussed this with several previous fellows when I was studying architectural history. Although no definite conclusion was reached, I still speculated that since some backboards were designed for rotating while others were fixed, opening the screen-gates at a specific ceremonial phase could strengthen the relationship between the ancestors and their descendants. Some residency fellows and I, with great effort, pushed the stuck screen-gates of the main hall’s secondary rooms open to enable them to move. The opening actions, as performative movements, had lead to spatial changes, the gates and space being actors.

《先祖戏台》

(屏门前舞蹈,表演者:韩京菁、郑宇轩)

Stage of Ancestors

(Dance in front of the Screen-gates. Performers: Han Jingjing & Zheng Yuxuan)

© Yolanda vom Hagen

屏门转轴

S

pindles of the S

creen-gates ©

木伏建筑研究所

我在第一进庭院中间设计了一组装置,作为舞台支点。粮站是村民对祠堂曾经真正被使用尚存的一丝记忆。我在网上找到了一张文革时期交粮食到粮站的照片。尽管不是郑村的景象,但大致应能反映当时的状态。村民用扁担挑着装满粮食的竹筐,密密麻麻地排队站在粮站的门口。

我试图通过这组装置营造出一个特殊的气氛,希望村民一进祠堂,就能被唤起关于粮站这一历史片段的记忆。我向当地竹匠借了竹篮、竹匾、竹筐等竹制品,村民慷慨地提供了稻谷、辣椒、大蒜等农产品作为道具。我在竹筐里堆满了稻谷,排在庭院的主道两侧,既形成了一个隐喻,也限定了表演区域。装置中间的部分由一个杀猪桶、一把梯子、一组板凳、两个竹匾组成,前面三样是同行的艺术家表演所用的道具。我选择了演员要使用的道具放在装置中,以促使演员和装置发生互动。

在表演中装置时而象征天平,时而被当作磨盘转动,时而又象征通天之 路,最后被拆散解构。我也建议装置中的稻谷、辣椒等在特定的时刻被抛洒向观众,它们也是演员,被舞者驱动发生运动。在我看来,一个舞美的置入,如果不被演员使用,那它便只是摆设,是演出多余的部分。舞美只有被演员使用,它才能真正整合入表演中的,才是有价值的。

I designed an installation placed in the centre of the main courtyard as the stage fulcrum, which responded to the villagers’ memory of the ancestral temple as a barn. I found a picture on the internet of collecting grain in the Cultural Revolution. Although it was not a scene of Zheng Village, it could generally reflect the situation decades ago. In the picture, the villagers carried bamboo baskets full of grain with shoulder poles standing in line in front of a barn. My design aimed to create a special atmosphere to recall the villagers’ memory of this historical harvest moment once they entered the temple. I borrowed bamboo baskets and trays from a local craftsman, and some villagers also generously provided agricultural products such as rice, pepper, and garlic as props. I piled rice in bamboo baskets and arrayed them on both sides of the axis road of the main courtyard, making a metaphor and defining the performance area. The central part of the installation consisted of a pig killing barrel, a ladder, a group of benches, and two bamboo trays, which were to be used by our fellow for performance. The installation symbolised a mill, a balance, and the heaven passage at different moments, and then it was disassembled. I chose the exact props that other actors would use to force the interactions between the performers and the installation. I also suggested that the rice and pepper be thrown to the audience at a certain time, which makes them object-actors driven by human dancers. In my opinion, without interacting with actors, a scenographic set is just a redundant decoration. Only through actors’ use can scenography be truly integrated into performances and show its great value.

交粮历史照片(匿名) A Historical Picture of Collecting Grains (Anonymous)

主庭院布置 The Scenographic Setting in the Main Courtyard ©

木伏建筑研究所

中心装置 The Central Installation

©Yolanda vom Hagen

《斩尾龙》

(装置互动,表演者:陈宇飞)

Tailless Dragon

(Interaction with the Installation. Performer: Chen Yufei)

© Yolanda vom Hagen

《祭祀之舞》(排练,装置互动,表演者:陈宇飞)

Worship Dance(Rehearsal.Interaction with the Installation. Performer: Chen Yufei)

© YolandavomHagen

《祭祀之舞》

(装置互动,表演者:丹艺)

Worship Dance

(Interaction with the Installation. Performer: Daniel Rojasanta)

© Yolanda vom Hagen

《祭祀之舞》

(装置互动,表演者:丹艺、陈宇飞)

Worship Dance

(Interaction with the Installation. Performers: Daniel Rojasanta & Chen Yufei)

© Yolanda vom Hagen

基于以上的思考,我提出了这次舞美的三个原则:

(1)表演尽可能做到双向,既面对观众又面对祖先,避免镜框式舞台的模式。

(2)让门成为演员,几道门构成了一个系统,每组需要在演出的特定节点开启或关闭。

(3)演员尽可能地使用庭院中的装置作为道具。

Based on the above ideas, I proposed three scenographic principles as follows: (1) The performing should be as bidirectional as possible, facing both the villagers and the ancestors and avoiding the mode of ’proscenium stage’. (2) Regarded as actors, three groups of gates should constitute a system, with each group opening or closing at a specific performative moment. (3) The actors should try their best to use the installation in the courtyard for props and make interaction.

空间表演解析(动图)

The Analysis of Spatial Performance (Animation) ©

木伏建筑研究所

在空间气氛的塑造上,第一进院落我并未作过多的介入,它应该是欢闹、自然、人世的,让表演自然而然地发生,让气氛自然而然地游走变化。

关于祖先牌位所在的第二进院落,在现实中大部分的时间里,龛位是整个祠堂里视觉上最为黑暗的区域,甚至带着些许阴冷。在演出中,我希望赋予这个区域一些不一样的气氛。这个区域的气氛应该和第一进院落有显著的区别,我尽量压暗了这个区域的光线,希望通过龛橱中透出的淡淡的暖黄灯光塑造出幽暗神秘的气氛,但又带着些许温馨。当龛门打开时,祖先牌位前闪烁着星星点点的烛火。我想让村民能够在这个空间中作稍许的停留,冥想片刻。或许他们能和祖先产生一些内心深处的对话,感受到祖先的守护。

In terms of shaping the spatial atmosphere, I did not intervene too much in the main courtyard because its atmosphere should be lively, natural and worldly, with the performance happening naturally and the atmosphere shifting smoothly. Regarding the space of the inner courtyard and inner hall where the ancestral tablets were located, for most of the time, the niche is the darkest area of the entire temple, making people psychologically feel cold. However, I hoped to give this area a different atmosphere from that of the main courtyard in the performance. I dimed the light to create a mysterious atmosphere through faint yellow light from the niche, sending warmness. When the shrine gates opened, the ancestor’s tablets were illuminated with twinkling candlelight. I hoped the villagers would stay in this space and meditate for a while, and perhaps they could have deep dialogues with their ancestors and feel the ancestral protection.

《我的故乡》

(第一进院落,表演者:顾晨莹)

My Hometown

(The Main Courtyard. Performer: Gloria Gu)

© Yolanda vom Hagen

《对话》

(第一进院落,表演者:方富全、丹艺)

Dialogue

(The Main Courtyard. Performers: Daniel Rojasanta & Fang Fuquan)

© Yolanda vom Hagen

祖先之光

(第二进院落)

Glory of Ancestors

(The Inner Courtyard)

©Hu Zhenhang

演出中屏门的开启产生的争议耐人寻味。村民对此有不同的态度,甚至一些团队成员也对此持保留的看法。在屏门打开后,最先冲入是孩子,然后是一些男性和中年女子。一些老年女性村民选择了离开,也许在她们看来,祖先的空间不应开放,自己也不宜进入。我不由想起演出台词中的一句女性的质问:“我的名字能写进族谱吗?”空间的变化激发并揭示出了不同观念的碰撞,或许这便是空间介入的有价值之处。

Opening the screen-gates was intriguing, because the villagers had controversial attitudes towards this action and even some fellows had their reservations about this. With the screen-gates’ opening, the children rushed in first, then men and middle-aged women.

However, a few elderly female villagers chose to leave the building; perhaps in their view, the ancestral space should not be opened to the public, and they should not enter. It reminds me of a females’ query in a line of the performance: "Will my name be written into the pedigree?" The transformation of space sparked and revealed collisions of different views, which probably is the value of spatial interventions.

《花·石·水》(表演者:韩雪)

Flower, Stone, and Water (Performer: Han Xue)

© Yolanda vom Hagen

伯纳德·屈米认为建筑不应当只是功能的也是事件的。维克多·特纳和理查德·谢克纳讨论了仪式和剧场的阈限性。当尘封多年的祠堂的大门再次被打开,发生的既是虚拟的戏剧表演,也是真真实实的村民的聚会和与祠堂的重新连接。在我看来,演出前对于祠堂的清扫也是我们这个团队对祖先表达的真实敬拜。一个颇有意味的细节是,演出次日,祠堂最外一道门,牌坊下破败许久的木栅栏门竟被维修了。剧场活动再造了乡村生活……

Bernard Tschumi believes that architecture should not be only functional but also event-oriented/based. Victor Turner and Richard Schechner both discuss the liminality of ritual and theatre. When the ancestral temple’s dust-laden entry gate reopened, what happened was not only a virtual drama but also a real gathering of villagers who reconnected with their ancestors. I saw our cleaning-up of the ancestral temple before the performance as our team’s real worship for the ancestors. An intriguing event was that the wooden fence entry gate, being broken for a long time, was repaired the next day of the performance. Theatre recreates rural life.

村民聚会 Gathering of Villagers

©汪钧

《西溪故事》(表演者:汪颖、顾晨莹)

A Story from Xixi (Performers: Wang yin & Gloria Gu)

© Yolanda vom Hagen

祭扫 Cleaning-up

©YolandavomHagen

大门修缮

The Maintanence of the Fence Entry Gate

©杨蕴真

海报 Poster

©陈欣茹

回顾视频 Recap Video

©王晟

项目信息

项目名称:《土地:戏·说》空间场域设计

项目设计&完成年份:2020 年

主创及设计团队:胡臻杭(主创)、韩雪(助理)、张琪丽(制图)

项目地址:安徽歙县郑村

客户:盘上海

客服

消息

收藏

下载

最近