查看完整案例

收藏

下载

翻译

Past lives: wetrackdown the most distinctive, weird and wonderful art exhibitionspaces aroundthe world

From resurrected churches to roller skating rinks and subterranean reservoirs, we reflect on the past lives, and reincarnations of the world’s most extraordinary contemporary art spaces. Explore the untold history of art.

Von Bartha

Past life: a lighthouse

Location: Copenhagen

Image:Carlsberg Archives

Von Bartha recently became the first international gallery to open a space in Copenhagen. Located at Pasteursvej 8, its distinctive building includes a listed former lighthouse (officially known as Kridttårnet) in the Carlsberg region of the city, developed for the brewer in the 19th century by founder Carl Jacobsen.

Exterior view of von Bartha gallery, Copenhagen. Photography: Leah Studinger

Marking its first location outside Switzerland, von Bartha’s new space continues the gallery’s track record of striking architectural transformations, with von Bartha’s original Basel space housed in a former petrol station. The new Copenhagen location comprises 75 square metres of gallery space with an outdoor courtyard for sculpture and was inagurated with group show,‘An Outline Taking Shape to Become a Profile’.

GES-2 House of Culture, V-A-C Foundation

Past life: a tram power station

Location: Moscow, Russia

Archival image of GES-2 building, a former power station built between 1904 and 1908. Image: Mosenergo archives

V-A-C Foundation’s GES-2 House of Culture, Moscow was one of the most hotly anticipated openings on the 2021 art calendar. Reimagined by Renzo Piano and over a decade in the making, the former power station is located on the Bolotnaya Embankment, a hotbed for industrial redevelopments and stone’s throw from the Kremlin. Built between 1904 and 1908 to power the city’s tram system, the building was designed in the Russian Revival style by architect Vasili Bashkirov.

Photography: Gleb Leonov

Piano’s space is a 41,000 sq m canvas of white and grey, save for the bold blue of the pipework, a hangover from the building’s previous life.GES-2 was founded on the idea of a Soviet House of Culture, and was inaugurated by Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson in December 2021. His performative work, Santa Barbara – A Living Sculpture, is a bold, theatrical piece examining the complex relationship between Russia and the US.

The Center for Contemporary Art, Tashkent

Past life: a diesel power station

Location: Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Top: Archival image (c. 1920) of the former diesel power station designed by Wilhelm Heinzelmann. Above: Installation view of ’Dixit Algorizmi’ at The Center for Contemporary Art Tashkent (CCAT)The building that now houses The Center for Contemporary Art Tashkent (CCAT) is where electrification of the city began, and where Uzbekistan’s contemporary art landscape is now being regenerated.Designed by architect Wilhelm Heinzelmann in 1912, the facility was a diesel power station operating Tashkent’s first tram line, and Tashkent City Enterprise of Electric Grids following the 1917 Russian Revolution. In 2019, a year after the building transferred to Uzbekistan’s ministry of culture, CCAT became the country’s first centre dedicated to modern and contemporary art, which aims to develop contemporary culture throughout Tashkent and Central Asia. Beyond exhibitions, the centre is a hub for performances, cinema screenings, art residencies and seminars.

Its recent exhibition, ’Dixit Algorizmi’ traced the roots of modern-day algorithms to the historic mathematician and Father of Algebra, Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwārizmī. Curated by Joseph Grima, the show featured work by artists, musicians, filmographers, architects, designers and theorists.

Public Tobacco Factory

Past life: a tobacco factory

Location: Athens, Greece

Top: Nikos Navridis, Try again. Fail again. Fail better, 2013,courtesy the artist, NEON and Bernier/Eliades Gallery. Installation View ’Portals’, Hellenic Parliament + NEON at the former Public Tobacco Factory. Photography © George Charisis.Above:Former Public Tobacco Factory – Hellenic Parliament Library & Printing House (pre-renovation)| Photography: © Fanis Kafantaris | Courtesy Hellenic Parliament & NEON

In the 19th century, tobacco served as one of Greece’s most important exports. In Athens, the Public Tobacco Factory, constructed in 1930 to cultivate this coveted crop, has recently been transformed into a stage for world-class international art. ’The former Public Tobacco Factory building is an iconic structure in the city centre, a symbol of the country’s path to industrialisation and, at the same time, a footprint of its architectural heritage,’ says Elina Kountouri, co-curator of the recent exhibition ’Portals’ and director of Neon, the non-profit arts organisation founded by collector and entrepreneur Dimitris Daskalopoulos who co-organised the show and renovated the historic building.

Glenn Ligon, Waiting for the Barbarians, 2021, Neon. Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery. Commissioned by NEON. Installation View ’Portals’, Hellenic Parliament + NEON at the former Public Tobacco Factory. Photography © Natalia Tsoukala, courtesy NEON

Though the story begins with tobacco and ends with world-class contemporary art, the shapeshifting industrial building has demonstrated versatility over its near-century history. It’s done time as a prison, been a Second World War air-raid shelter, housed Romanian refugees, been home to the Greek Cabinet Office, the Ministry of Finance, and its present occupant, the Hellenic Parliament, with which Neon collaborated for ’Portals’, which includes new commissions by Glenn Ligon, Duro Olowu, Teresa Margolles, Michael Rakowitz, Danh Vō and Chrysanthi Koumianaki.

Fruitmarket gallery

Past life: a fruit and vegetable market

Location: Edinburgh, Scotland

Top: Exterior of the Fruitmarket during exhibition, ’Watermarks: Robert Callender and Elizabeth Ogilvie’, 1980. Above: Installation view, Fruitmarket, ’Karla Black: Sculptures (2001–2021) details for a retrospective’. Photography: Tom Nolan

There’s at least one clue in the name: this Edinburgh art centre was once home to a fruit and vegetable market. The gallery combines two former market buildings: one built in 1889, and one in 1938. The latter was converted into a gallery in the 1970s by John L Patterson, with one part serving as a Scottish Arts Council venue.

The Fruitmarket soon became a hub for the who’s who of 20th-century art, with solo shows by the likes of Richard Hamilton, Frank Stella, Willem de Kooning, Henri Cartier-Bresson and David Hockney. In 2021, the Fruitmarket still finds itself on the cutting edge of contemporary art following a two-year redesign, expansion and refurbishment at the hands of Reiach and Hall Architects. The vast industrial gallery reopened in 2021 with a reimagined retrospective by Turner Prize-nominated artist Karla Black.

MAAT Museum

Past life: Athermal power station

Location: Lisbon, Portugal

Historical photograph of the Central Tejo power station, Lisbon. Photography: Kurt Pinto, courtesy of EDP Foundation

On the banks of the River Tagus, Lisbon, there’s a conversation happening between two entirely different buildings. Though a century apart, they do have one thing in common: the Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology.

Built in 1908, Central Tejo was a thermal power station that supplied the entirety of Lisbon with electric power, operating non-stop between 1909 to 1954. The iron and brick-covered building, typical of late 19th-century ‘electricity factories’, draws on a mix of influences, from Art Nouveau to classicism. In 1990, it opened to the public as the Electricity Museum, offering a journey through the history and evolution of electricity production, technological feats in renewables, and the EDP Foundation art collection, dedicated to contemporary Portuguese artists.

Installation view of ’Rehearsal for a Community’,MAAT – Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology.Photography: Daniel Malhão

Also on the industrial EDP Foundation campus, but at the opposite end of the architectural spectrum, is a building housing the Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology (MAAT). Designed by British architecture studio AL_A (Amanda Levete Architects) and opened to the public in 2016, the low-slung structure, comprising 15,000 three-dimensional tiles, can be walked over, under or through, and reflects the institution’s convergence of contemporary art, architecture and technology. Among those who have exhibited at MAAT are Pedro Reyes, Lawrence Weiner, Grada Kilomba and Tomás Saraceno.

Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art

Past life: A flour mill

Location: Gateshead, UK

Aerial view of theJoseph Rank Baltic flour mill in Gateshead. Courtesy BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead

On the south bank of the River Tyne in Gateshead sits a former flour mill re-imagined as the UK’s largest contemporary art institution. Completed in 1950, it was built by food giant Rank Hovis to a late-1930s design by architects Gelder and Kitchen. The mill closed in 1981 and lay derelict for over two decades. The idea of Baltic as we know it today was conceived in 1991 when Northern Arts (now Arts Council England North East) announced plans for a ‘major new capital facilities for the Contemporary Visual Arts in Central Tyneside’.

Under the guidance of Baltic’s inaugural director Sune Nordgren, the focus officially shifted from flour to contemporary art. Construction began in 1998 spearheaded by Ellis Williams Architects and comprising six main floors, three mezzanines, and 3000sqm of arts space including studios, a cinema/lecture space, shop, library, archive and rooftop restaurant. In 1999, there was a pause in construction, during which time the building got its first taste of art. Anish Kapoor was commissioned to createTaratantala, a colossal site-specific artwork, that occupied the vast, void-like space.

Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art opened in 2002. The inaugural exhibition, ‘B.OPEN’, featured work by Chris Burden, Carsten Holler, Julian Opie, Jaume Plensa and Jane & Louise Wilson. Since then, Baltic has launched an artist award, and presented over 226 exhibitions of work by 476 artists of 64 nationalities including Holly Hendry, Judy Chicago, Ryan Gander, Lubaina Himid, Adam Pendleton and Lorna Simpson.

Anish Kapoor,Taratantala (1999). Photography:John Riddy

Holly Hendry,’Wrot’, installation view, 18 February – 24 September 2017.Photography: John McKenzie. © 2017 BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art

Wiels

Past life: A brewery

Location: Brussels, Belgium

The facade of the Wielemans-Ceuppens brewery in1930. Photography:Willy Kessels

In 1862, following attempts at trading in baked goods and cloth, the Belgian Wielemans-Ceuppens dynasty ventured into beer. Following rapid expansion and a quest for innovative techniques, the family invested in a brand new flagship brewing hall, one that would become the largest in Europe and a landmark on the Brussels urban landscape. Designed in 1930 by architect Adrien Blomme and praised as a ‘perfect example of modernism’ the striking building (also known as the Blomme building or the Wielemans tower) still brims with traces of its industrial past.

During 2005-2008 renovations, some of the brewery’s original operational features were restored, such as copper vats and tiling in the brewing hall. In 2007, the building took on new life as a centre for contemporary art. In addition to 19,000 sq ft of exhibition space, the building hosts an auditorium, studio workshops for artists-in-residence, and a café and bookshop in the titanic brewing hall. Among those who have presented work in this laboratory of contemporary art are Wolfgang Tillmans, Yayoi Kusama, Franz Erhard Walther,Mark Leckey, Luc Tuymans and Rita McBride.

Above: Inside the brewing hall-turned-café of Wiels in 2018. Photography: Alexandra Bertels.

Below: Installation view of Franz Erhard Walther’s exhibition at Wiels in 2014. Photography: Sven Laurent

TJ Boulting

Past life: an ironmongery and sanitaryware manufacturer

Location: Fitzrovia, London

Exterior view of TJ Boulting gallery, which was previously home to furnishing ironmongers TJ Boulting & Sons

Originally founded in 1808, furnishing ironmongers TJ Boulting & Sons were responsible for the manufacture of range and stoves alongside gas, electrical, sanitary and hot water engineering. Sited on a corner in the heart of Fitzrovia, its Arts and Crafts building is still inscribed with the original Art Nouveau lettering in gold and green mosaic tiles. The company, which moved into the building in 1903, has something of an intriguing claim to fame, said to have fitted the first flushing loo in Windsor Castle, before the more widely known Thomas Crapper made his mark.

In 2011, inspired by the building’s roots, Gigi Giannuzzi and current director Hannah Watson established TJ Boulting as the new gallery space of publishing house, Trolley which specialises in photography, photojournalism and contemporary art titles. Over the last decade, the gallery has carved a reputation for dynamic shows of emerging and mid-career artists. Previous exhibitions include Dominic Hawgood’s shape-shifting ‘Casting Out The Self v3.1’ and ‘Birth’, curated with Charlotte Jansen.

Above: Installation view ofDominic Hawgood ’Casting Out The Self v3’, 2020. Below: Installation view ofHelenA Pritchard, ’Enmeshed Worlds’, which will reopen once lockdown restrictions lift on 12 April

La Patinoire Royale - Galerie Valérie Bach

Past life:a roller skating rink

Location: Brussels, Belgium

Archival architectural illustration of the facade of the Royal Skating rink in Brussels, dated 1877. From the archives of the Town Planning Department, Municipal Archives of Saint-Gilles

This is a gallery with a big claim and quite a few past lives. Constructed in 1877 as Royal Skating, it became one of the world’s first roller skating rinks, in a time when popularity for the recreational sport was at an all-time high. In 1900, roller skate wheels turned into car wheels as the space transformed into a Bugatti garage, and later a weapons depot during World War Two. Built in an ornate Neoclassical style, the building’s facade is punctuated by distinctive circular and arched windows, flooding the interior space with a sea of natural light. In 2015, gallerist Valérie Bach acquired the space, enlisting John-Paul Hermant architects to transform it into a hub for Belgian and international Modern and contemporary art with a focus on kinetic installations and abstraction. The 3,000 sq m internal space, masterminded by Pierre Yovanovitch, has since hosted striking contemporary art interventions by the likes of Joana Vasconcelos, Carlos Cruz-Diez and Martine Feipel and Jean Bechameil.

Above: the grand hall of La Patinoire Royale. Photography: Tanguy Aumont, Airstudio for the Patinoire Royale.

Below:Exhibition view Martine Feipel & Jean Bechameil ‘A Hundred Hours from Home’. Courtesy of Galerie Valérie Bach

KW Institute for Contemporary Art

Past life: a margarine factory

Location: Berlin, Germany

Courtyard of Kunst-Werke Berlin, 1991.Photography: Uwe Walter

KW is widely known as a cultivator of radical contemporary art, but one might be less familiar with the unexpected past life of its building. The original Baroque structure was built for residential purposes in 1794 and remains one of the oldest buildings in Berlin’s Auguststraße. Its transverse wing was built in 1877 for industrial use, most recently, as a margarine factory called Berolina Margarinefabrik during the German Democratic Republic era.

In 1991, Klaus Biesenbach, Alexandra Binswanger, Philipp von Doering, Clemens Homburger, and Alfonso Rutigliano saw the potential in this crumbling factory as a platform for provocative avant-garde art. Its global reputation has since been cemented by landmark thematic shows including ‘Berliner Chronik’ (1994); ‘One on One’ (2012/13); ‘Fire and Forget. On Violence (2015)’; and ‘The Making of Husbands: Christina Ramberg in Dialogue’ (2019/2020) and major solo shows by Kader Attia, Ceal Floyer, Carsten Höller, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Petrit Halilaj and Adam Pendleton. To hail the institution’s 30th anniversary in 2021, KW hosteda series of new commissions and exhibitions by the likes of Renée Green and Susan Philipsz. Responding directly to the building,artist Sissel Tolaas created a limited-edition soap composed of particles collected at KW.

Petrit Halilaj, The places I’m looking for, my dear, are utopian places, they are boring and I don’t know how to make them real; installation view of the 6th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, Berlin 2010; Courtesy the artist; Photography: Uwe Walter

Lynn Hershman Leeson, First Person Plural, the Electronic Diaries of Lynn Hershman, 1984-96 (in four parts); installation view in the exhibition First Person Plural at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin 2018; Courtesy the artist; Photography: Frank Sperling

Pirelli HangarBicocca

Past life: a locomotive factory

Location: Milan, Italy

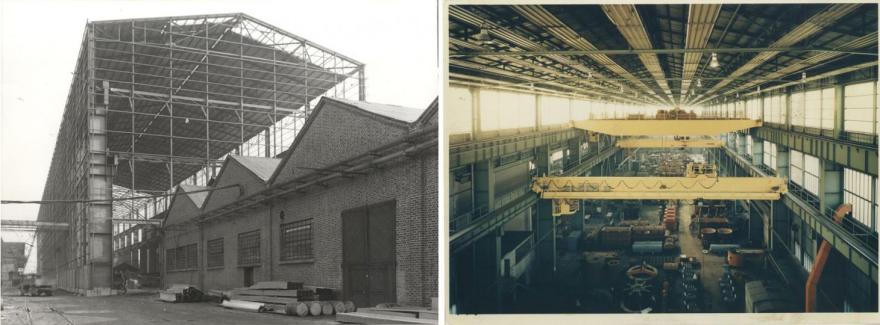

Left: The building of Breda Elettromeccanica company’s new shed, 1963-64. Right: inside the shed, taken in the second half of the 60s. Courtesy Fondazione Isec, Archivio storico Breda

When it comes to scale, there’s nowhere quite on par with the sheer enormity of Pirelli HangarBicocca. The site once occupied one of the most burgeoning industrial centres in Milan, spearheaded by engineer Ernesto Breda in 1886. This vast complex of factories, which included tyre manufacturing giant Pirelli, produced railway carriages, electric and steam locomotives and was later adapted to manufacture aeroplanes and projectiles during the First World War effort. One factory was HangarBicocca, a gargantuan 15,000 sq m space comprising three main areas.

In 2004, after a decade of neglect, Pirelli transformed the space into a non-profit art foundation staging major annual solo shows and permanent installations. Many indicators of the building’s industrial past are still intact. The 30-metre-high, 9500 m sq Navate, constructed between 1963 and 1965 still has visible traces of the rails used to test locomotives, and now hosts Anselm Kiefer’s monumental permanent installation The Seven Heavenly Palaces, commissioned for the foundation’s opening. There’s no doubt that a space like this takes a particular blend of courage, ambition and vision to fill. Among those who have surmounted the task to jaw-dropping effect are Philippe Parreno, Ragnar Kjartansson, Kishio Suga, Marina Abramović, Joan Jonas and Cerith Wyn Evans.

Exterior view of the Pirelli HangarBicocca art foundation today. Courtesy Pirelli HangarBicocca. Photography: Lorenzo Palmeri

Cerith Wyn Evans ’….the Illuminating Gas’, exhibition view at Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan. Photography: Agostino Osio

Cisternerne

Past life: a subterranean reservoir

Location: Copenhagen, Denmark

1889 illustration of plans for the Cisternerne underground reservoir in Copenhagen.Image credit: Slots-og Kulturstyrelsen

If it weren’t for the world-class art installations, the uncanny depths of Copenhagen’s Cisternerne might be akin to a cathedral crypt or The Chamber of Secrets. The ex-subterranean reservoir was built from 1856-1859 to improve the water supply to the Danish capital and became defunct in 1933. It was deserted for decades before starting a unexpected new life in 2001 as The Museum of Modern Glass Art. In 2013, it was acquired by the Frederiksberg Museums and has since played host to ambitious annual art installations with globally-renowned contemporary artists. As exhibition backdrops go, there is nowhere quite like the challenges of the Cisternerne. Among those who have stepped up to the task to dizzying effect are Jeppe Hein, Eva Koch, Ingvar Cronhammar, Superflex, architect Hiroshi Sambuichi and most recently, Tomás Saraceno.

Above, The vacant Cisternerne. Photography:Johan Rosenmunthe. Below, TomásSaraceno’s installation,EventHorizon atCisternerne. Photography:Torben Eskerod

E-Werk

Past life: a coal power station

Location: Luckenwalde, Germany

E-WerkLuckenwalde, c.1920. Courtesy of E-Werk and Paul Damm

The transition from power station to art gallery is a fairly well-trodden path, and though E-Werk may not have the show-stopping scale of Tate Modern or Shanghai’s Power Station of Art, unlike the aforementioned institutions, it still generates power. The building was constructed in 1913 as a coal power plant and shuttered its doors soon after the fall of the Berlin Wall. 30 years later, the space was resurrected by Artist Pablo Wendel and his not-for-profit arts organisation, Performance Electrics, as explored in Wallpaper’s October 2019 issue (W*247). E-Werk offers residential programmes, workshops, studio space for artists, exhibitions, and its own, patented power source: Kunststrom (art electricity) harnessed through wood chip-burning machines still compatible with the building’s pre-existing infrastructure - an electric fusion of art and power.

Above, E-WerkLuckenwalde Turbine Hall, c. 1920. Courtesy of E-Werk and Paul Damm. Below, E-Werk’s Turbine Hall today, which plays host to a roster of performance artists. Photography: Stefan Korte, for the October 2019 issue of Wallpaper*.

Planta

Past (and present) life: an industrial gravel pit

Location: Lleida, Spain

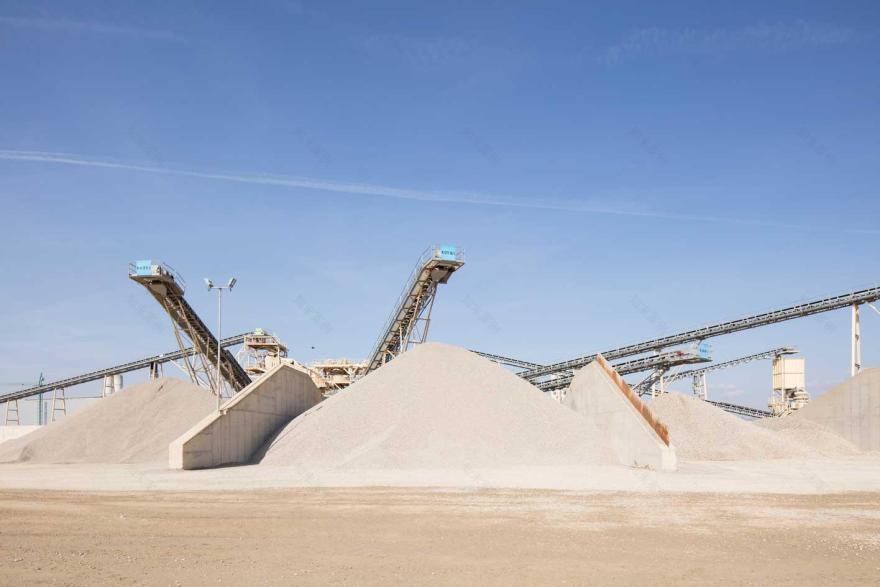

The industrial landscape surrounding Planta, an innovative contemporary art project in rural Catalonia. ©Fundació Sorigué, 2020

An industrial complex on the northern edge of rural Catalonia is perhaps the last place one might expect to stumble across an Anselm Kiefer, or a Bill Viola. But coexisting with the daily buzz of lorries and cranes shuttling around mounds of gravel, are spaces dedicated to site-specific contemporary art. Planta is an innovative project on the intersection of art, science, architecture, and enterprise. It’s managed by Fundació Sorigué, the foundation of the Sorigué Business Group, who, aside from a zest for contemporary art, focus on material science research and sourcing sustainable building materials. Sites include an enormous hangar which plays host to Spanish sculptor Juan Muñoz’s Double Bind (previously exhibited in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall) and an ex-air raid shelter (constructed during the Spanish Civil War) which houses a video installation by Bill Viola. Others who have exhibited in this lunar-like industrial landscape include Tony Cragg, William Kentridge, and a project with Chiharu Shiota is in the pipeline.

Above, Installation view ofDouble Bind, by Juan Muñoz at Planta. Below, Inside theAnselm Kiefer Pavilion at Planta.©Fundació Sorigué, 2020

König Galerie –St. Agnes Church

Past life: a brutalist church

Location: Berlin, Germany

Exterior viewof König Galerie’s St Agnes Church. Photography:RomanMärz

König Galerie has a track record for tracking down unusual gallery spaces. Their London space was, after all, an underground car park until 2017. But six years before then, they took on the challenge of turning the heritage-listed St. Agnes – a former Catholic church and built in 1967 by German architect and post-war modernist Werner Düttmann – from dilapidated brute into a striking stage for international contemporary art. Sited in the Kreuzberg area of Berlin, St. Agnes comprises a former chapel and nave which were artfully transformed from church to gallery by architect Arno Brandlhuber. Among those who have taken full advantage of the gallery’s light, lofty and utterly monumental proportions are Claudia Comte, Elmgreen & Dragset, Camille Henrot and Katharina Grosse.

Above, Architectural model of St. Agnes Church by architectural studio Arno Brandlhuber who renovated the space in 2015. Courtesy of König Galerie Berlin and the Brandlhuber+ Team. Below, Installation view of JoseDávila ’TheMomentofSuspension’ in the Nave of St Agnes Church at König Gallery, Berlin. Photography: Roman Maerz

Arquipélago

Past life: an alcohol factory

Location: Ribeira Grande, São Miguel, Portugal

Exterior view of one of Arquipélago’s buildings before renovations

In 2015, a 122-year old industrial volcanic stone and timber building in the town of Ribeira Grande on the Portuguese island São Miguel Island went from alcohol factory, to ‘culture factory’. The building was reborn as the Arquipélago Centre for Contemporary Arts, an interdisciplinary creative hub, at the hands of Portuguese architects Menos é Mais Arquitectos Associados and João Mendes Ribeiro.Located in the middle of the Atlantic, The Azores are known as a portal between Europe and the Americas. The centre takes its name from the nine islands that form the archipelago, and has a mission to ‘observe, stimulate, disseminate’ through a programme of visual art exhibitions, workshops, performances, concerts and artist residencies.Arquipélago is a harmonious, and forward-looking fusion of geography, eras and creative disciplines.

Top, In 2015, the former alcohol and tobacco factory was transformed in a art and cultural hub by Portuguese architects Menos é Mais Arquitectos Associados and João Mendes Ribeiro. Bottom, Installation view of the 2018 group show, ’SonicGeometry’, at Arquipélago picturing work by Jonathan Saldanha.

客服

消息

收藏

下载

最近