查看完整案例

收藏

下载

"Main street design is a grand challenge of the 21st century as urban neighborhoods seek to create sustainable, resilient, and beautiful public spaces. This project highlights what careful design can contribute to the making of place, not a lot of jewels or distractions, but simple, clear, and elegant design of public space. The emphasis on thresholds, nodes, and shared spaces is exactly what urban design needs to engage" – 2014 Awards Jury

“随着城市社区寻求创造可持续的,适应力强的而又美丽的公共空间,主街设计成为二十一世纪的一个重大挑战。这个项目强调了精心设计能够营造出怎样的场所,并不需要过多的浮华装饰,而是简单,明了而又典雅的公共空间设计。项目所强调的阀口,节点,和共享空间正是城市设计需要去参与的。” ——2014获奖评审词

The Creative Corridor: A Main Street Revitalization for Little Rock by University of Arkansas Community Design Center and Marlon Blackwell Architect

,更多请至

University of Arkansas Community Design Center and Marlon Blackwell Architect via:asla

创意走廊通过对文化艺术,而不是其传统的零售商店的聚拢,改造了一个四个街区的濒危历史性城市中心主街。创意街区的目标是在对以艺术为导向的工作与居住环境混合使用的基础上建立自己的可识别性。设计的方法是把走廊重新塑造成一个节点,并且利用都市化的街景——景观建筑,生态工程,公共空间配置,临街系统以及其他的城市景观元素。

The Creative Corridor retrofits a four-block segment of an endangered historic downtown Main Street through aggregation of the cultural arts rather than Main Street’s traditional retail base. The goal is to structure an identity for the Creative Corridor based upon a mixed-use working and living environment anchored by the arts. The design approach restructures the corridor into a node utilizing the urbanism of streetscapes—landscape architecture, ecological engineering, public space configurations, frontage systems and other townscaping elements.

▼Unlike roads, which efficiently move traffic from one point to another, streets are platforms for capturing value. A well-designed street provides non-traffic social functions related to gathering, assembly, recreation, ecology, and aesthetics.

不像车型道路把交通从一点转移到另外一点,街道是捕获价值的平台。好的街道设计可以提供非交通性社会功能,比如聚会,集会,娱乐,生态和审美。

Photo Credit: University of Arkansas Community Design Center + Marlon Blackwell Architects

从商业到文化和居住使用上的目标和目的

对这片被忽略的旧城区主街的改造,通过聚拢现在分散在整个大都市圈的文化机构,来催化和设计出一种与之前基于传统零售业不同的综合性用地方式。这个公开委托的设计为提供了一种目前小石镇尚未具备的生活方式,把居住,工作和文化结合到一起。后者包括为交响乐,芭蕾舞,艺术中心,视觉艺术家,剧院,舞蹈以及烹饪艺术提供的展示或创作空间。这样一来,餐厅,公展和教育三足鼎立。设计方案依靠街景城市主义——景观建筑,生态工程,公共空间配置,临街系统和其他城市景观元素,确保了在不同发展时期有连贯的可识别性。

完整街道

本项目以交通优先权来密集华非交通功能,以便能够在一个混合式居住环境内,支持新的文化艺术的侧重点。完整的街道是为所有不同年龄和能力的使用者设计的,包括行人,自行车,摩托车和公共交通的使用者,它是成功创造出综合使用环境不可或缺的一部分。设计阶段式引入该城市并不多见的公共空间——集成发展式低能耗低排放灰水处理系统,共享式街道配置,自行车道,以及一个配有辅助设备的联合运输式轨道公交广场。共享街道配置与新式城市景观系统一起把公共空间与私人空间连接到一起,形成了一个支持创新型经济发展的新的步行功能的层次。

低能耗低排放发展式(LID)街道景观

街道景观的设计,在社会和城市功能之外还添加提供了生态功能。设计的LID处理系统——生态型灰水处理——把美国环保局的《绿化美国首都》研究报告扩展应用到主街的设计上。绿树成荫的大道与共享街道景观相结合了17处获得认可的生态系统服务——包括大气调节,(洪水)干预式调节,水控制,泥沙控制,养分循环,废物处理,植物授粉,栖息地等等。林荫大道就像一个大树箱型过滤器,设有渗透系统来灌溉原声的低水量需求景观,这里还能用作户外用餐和集会的场所。街道本身变成了一个生态资源,在灰水排放到临近阿肯萨斯河的下水道之前,污染源就已经被当场代谢掉了。

环境/社会数据与分析方法

小石镇的城市振兴战略是被遗弃的城市肌理内一些自给自足的节点。主街的衰落是城市热衷于获得始于1950年代的联邦政府城市更新资金的牺牲品。“小石镇中心城市更新项目”最终成为了全国性城市社区空巢化的模型:580英亩市中心遭到拆除,包括471栋商业建筑(全市193,000栋建筑里的超过1600栋也遭拆除);1970年,城市人口密度从每英亩18人下降到每英亩5人。一些市中心地区的人口密度下降多达百分之七十五。

降水量用来支持绿色街道设计是经过生态环境工程师在Hydraflow软件里设置了两年的设施使用情况来模拟的。设施配备了耐寒类植物和既耐旱也耐水的生长主根的树木。

设计的角色和选择的考虑

附近中央商务圈的大型公司发展是外来入侵的元素。项目超越了简单遵守历史保护规范和街区美化,而是提出了与大公司的建筑业主一起对可适应性的重复使用经济性作出反应的改造方案,这些大型过公司之前还在对具有历史的主街结构进行拆除。地区根深蒂固的产权文化让规范对文化遗产的保护变得行不通。相反,通过道路,拱廊商场,城市门廊,以及露天剧场这些让人找回主街的场所感的元素的发展,一个灵活的城市景观平台可以去沟通相互冲突的建筑传统——新与旧,实与虚,大与小。

公众参与和项目实施

项目规划获得了美国环保局和能源局的资金支持,让六年时间内,超过三十家机构的公私伙伴与合作成为可能。城市主街工作组和业主,与统一搬迁到主街的当地主要文化艺术团体一起参与到设计过程中。私有机构掌管着建筑合同或是正在施工的翻新工程(超过200个住宅单元)中超过一亿六千万美金的资金,其中也包括租给文化团体的首层空间。LID街区景观的第一阶段工程于2014年三月开工。

项目管理

市长办公室在城市规划人员与顾问的协助下对设计展开实施。项目的公共改进部分涉及对LID景观的落实。美国环保局和阿肯萨斯自然资源委员会将负责为此提供资金。MetroPlan(阿肯萨斯中央区域交通管理部门)为创意走廊的轨道交通的改善建立了时间表。

▼ Site Plan: The Creative Corridor employs three phases to create a node.

Nodes provide a sense of centrality and opportunity for social life, countering the dominance of mobility in corridors. Each phase can be accomplished in succession or all at once as political will permits.

总平面:创意走廊利用三个阶段来创造出节点。

节点提供了中心感,以及为社会生活的提供了舞台,这与走廊占主导地位的流动性是相反的。每个阶段可以相继实施,或者在政策允许的情况下一次过完成。

Photo Credit: University of Arkansas Community Design Center + Marlon Blackwell Architects

▼ Architectural guidelines aren’t politically feasible. Townscaping elements like arcades, marquees, and stormwater management landscapes bridge street and building interiors.

Townscaping negotiates conflicting building traditions—historic and contemporary—rather than rely on historically-inspired guidelines.

建筑指引是不受政治影响的。城市景观元素,像是巷道,帐篷和雨水管理景观把街道和建筑内部想连接。城市景观在沟通这项目冲突的建筑传统——历史的和当代的——而不是单纯依赖基于历史风格的设计指导。

Photo Credit: University of Arkansas Community Design Center + Marlon Blackwell Architects

▼ The first thing we do is create gateways. Establish two urban rooms using pedestrian tables. These kinds of shared street strategies privilege a pedestrian environment supportive of non-traffic functions like outdoor dining and theater gathering.

我们做的第一件事就是创造关口。用行人平台建立了两个城市房间。三种街道共享策略让支持非交通功能,例如户外晚餐和剧院聚会的这种步行环境获得了优先权。

Photo Credit: University of Arkansas Community Design Center + Marlon Blackwell Architects

▼ Urban rooms with street furniture, architectural pavement, and landscapes are made of rustic and manicured plant palettes akin to an urban pocket park.

Tables are made from a modular suspended pavement system to support infiltration and tree growth.

城市房间,街道家具,建筑铺设,最后是或质朴或修剪过的景观像是城市的小型角落公园一样。桌子创自一个模数化悬挂铺设系统,以支持地表渗透和树木的生长。

Photo Credit: University of Arkansas Community Design Center + Marlon Blackwell Architects

▼ Gateway rooms sponsor non-traffic social functions unlikely in the existing corridor.

关口空间支持着现有走廊内不可能发生的非交通社会功能。

Photo Credit: University of Arkansas Community Design Center + Marlon Blackwell Architects

▼ We recycled street lighting and made it public art that marks entry.

Light gardens consisting of street lights recycled from Little Rock neighborhoods portray an urban history otherwise left unnoticed.

我们废物利用街灯,把他们做成了入口位置的公共艺术。灯光花园由从小石镇社区回收利用的街灯组成,如果没有它们在这里描绘着城市的历史,城市过去很容易就被遗忘了。

Photo Credit: University of Arkansas Community Design Center + Marlon Blackwell Architects

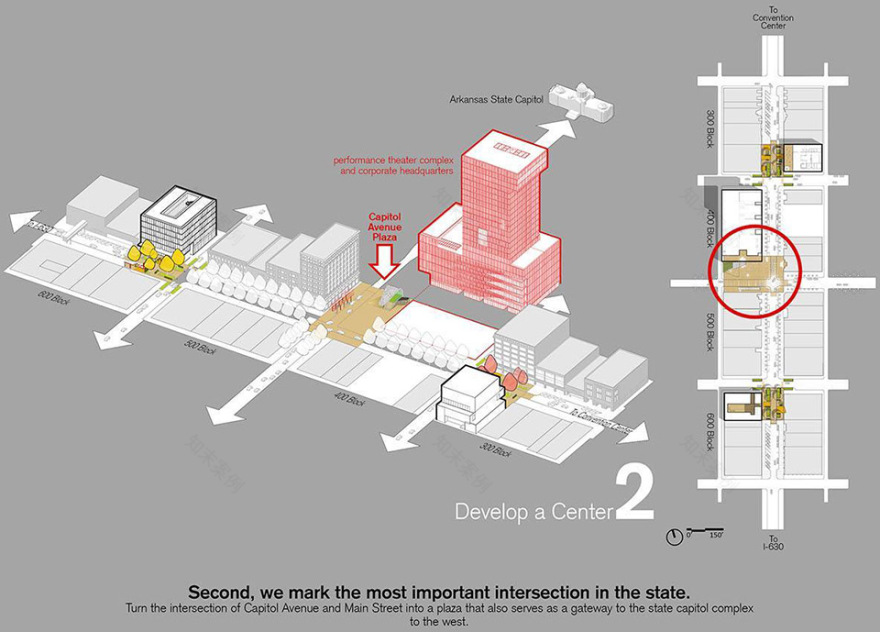

▼ Second, we mark the most important intersection in the state.

Turn the intersection of Capitol Avenue and Main Street into a plaza that also serves as a gateway to the state capitol complex to the west.

第二,我们标示出该阶段最重要的交汇处。把首都大道与主街的交汇处转变成一个广场,同时也作为该阶段通向西面州府综合楼的一个关口。

Photo Credit: University of Arkansas Community Design Center + Marlon Blackwell Architects

▼ The Capitol Avenue Plaza celebrates this important crossroads.

This node houses an elevated lawn/amphitheater, public transit stop, portecochere, light garden, and public art, to create an iconic and memorable room for assembly.

州府大道广场欢庆着这个重要的交叉路口。这个节点容纳了架高草坪/剧院广场,公共交通站点,门廊,光束花园,和公共艺术,来创造出一个值得记忆的标志性聚集空间。

Photo Credit: University of Arkansas Community Design Center + Marlon Blackwell Architects

▼ The energy of the street is pulled up through the architecture.

The plaza as a room mediates between new and old structures, as well as big and small scales.

建筑提升了街道的活力。作为空间的广场中和了新旧建筑和大小建筑之间的矛盾。

Photo Credit: University of Arkansas Community Design Center + Marlon Blackwell Architects

▼Third, we thicken the western edge using a pedestrian allee.

Link phases one and two with a Pedestrian Promenade that functions as a Low Impact Development (LID) infrastructure featuring ecologically-based stormwater management.

第三,我们用一条步行道来加厚了西面的边缘。行人路起着LID基建的作用,具有生态灰水处理。

Photo Credit: University of Arkansas Community Design Center + Marlon Blackwell Architects

▼ The US EPA gave us money to do this!

LID delivers many of the 17 recognized ecological services found in healthy ecosystems—atmospheric regulation, disturbance (flooding) regulation, erosion control and sediment retention, nutrient cycling, recreation, pollination, habitat, etc.

美国环保局为项目提供资金!

LID提供了17处获得认可的健康生态系统服务——包括大气调节,(洪水)干预式调节,水控制,泥沙控制,养分循环,废物处理,植物授粉,栖息地等等。

Photo Credit: University of Arkansas Community Design Center + Marlon Blackwell Architects

▼ The LID treatment landscape is designed as an extension of the indoor spaces.

The Pedestrian Promenade is a highly-productive water management landscape that accommodates public activities and gatherings in support of cultural and residential functions.

LID处理景观设计的像是室内空间的延续。行人路是个具有高度生产力的水处理景观,同时也容纳了公共活动和集会,为文化和居住功能提供了支持。

Photo Credit: University of Arkansas Community Design Center + Marlon Blackwell Architects

▼ Like a supersized tree box filter, the Promenade infiltrates and treats urban stormwater runoff before it is discharged through storm sewers into the Arkansas River.

行人路像个巨大的树木过滤器,把城市灰水在被排放到阿肯萨斯和之前就处理掉。

Photo Credit: University of Arkansas Community Design Center + Marlon Blackwell Architects

▼Boardwalk components in the Promenade integrate a public art network for The Creative Corridor.

人行步道的宽走道部分为创意走廊整合了一个公共艺术系统。

Photo Credit: University of Arkansas Community Design Center + Marlon Blackwell Architects

Indeed, a distinctive and legible environment not only offers security but also heightens the potential depth and intensity of human experience.

实际上,一个独特而清晰可读的环境不但提供了安全性,也加大了人类生活经验的潜在深度和密度。

Photo Credit: University of Arkansas Community Design Center + Marlon Blackwell Architects

Goals and Objectives From Commercial to Cultural and Residential Uses

Catalyzed by the aggregation of cultural organizations now scattered throughout the metropolitan area, this reclamation of a neglected historic Main Street proposes a land-use mix different from Main Street’s traditional retail base. This publicly-commissioned plan provides an affordable downtown living option presently unavailable in Little Rock combining residential, work and culture. The latter includes instruction/production space for the symphony, ballet, arts center, visual artists, theater, and dance, as well as a culinary arts economy that triangulates restaurants, public demonstration, and education. To ensure a coherent identity among different eras of development, design solutions rely on the urbanism of streetscapes—landscape architecture, ecological engineering, public space configurations, frontage systems and other townscaping elements.

Complete Streets

The project intensifies non-traffic social functions within the right-of-way to support a new cultural arts concentration within a mixed-use living environment. Complete Streets, designed to safely accommodate all users—pedestrians, bicyclists, motorists, and public transit users of all ages and abilities—are necessary components in the creation of successful mixed-use environments. The plan phases introduction of public spaces unfamiliar to the city’s public works—an integrated Low Impact Development (LID) stormwater treatment network, shared street configurations, bicycle boulevards, and an intermodal rail transit plaza with performance facilities. Shared street configurations with novel townscaping systems connect public and private spaces to frame a new layer of pedestrian functions supportive of a new creative economy.

Low Impact Development (LID) Streetscapes

Streetscapes are designed to deliver ecological services in addition to social and urban services. The proposed LID treatment network—ecologically-based stormwater runoff management—expands upon recommendations from US EPA’s Greening America’s Capitals study for Main Street. A tree-lined Promenade and shared street landscapes combine to deliver many of the 17 recognized ecosystem services—atmospheric regulation, disturbance (flooding) regulation, water regulation, sediment control, nutrient cycling, waste treatment, pollination, habitat, etc. Like a giant tree box filter, the Promenade feature an infiltration system planted with native xeriscapes that also house outdoor dining and gathering spaces. The street becomes an ecological asset, metabolizing water pollutants on site before runoff is discharged through storm sewers to the nearby Arkansas River.

Environmental/Social Data and Methods of Analysis

Urban revitalization strategies in Little Rock occur as self-sufficient nodes within a fabric of abandonment. Main Street’s decline was a victim of the City’s zealousness in securing federal urban renewal funds beginning in the 1950s. The Central Little Rock Urban Renewal Project eventually became a national model for urban neighborhood clearance: 580 acres of the downtown were demolished, including 471 commercial buildings (more than 1600 buildings total in a city of 193,000); and population density dropped from 18 people per acre to five in 1970. In some downtown neighborhoods the population dropped 75 percent.

Stormwater loading to support green street design was modeled by ecological engineers using Hydraflow software with facilities designed to support two-year events. Facilities are staffed with drought-tolerant plant guilds and trees that grow taproots, which can withstand water retention as well as drought.

Role of Design and Consideration of Options

Large corporate development from the adjacent CBD is an invasive species. The project offers a retrofit program beyond historical codes and street beautification responsive to the economics of adaptive reuse with corporate property owners who have recently demolished historic Main Street structures. The region’s entrenched property rights culture makes codes for legacy protection unfeasible. Rather, a flexible townscaping platform negotiates conflicting architectural traditions—between new and old, masonry and glass, and large and small—through the development of allees, arcades, urban porches, and amphitheaters that reclaim Main Street’s sense of place.

Public Participation and Project Implementation

Project planning was funded through grants from the US EPA and NEA, enabling public-private partnerships and collaboration from more than 30 organizations over a six-year period. The City’s Main Street Task Force and property owners participated in design workshops with the region’s principal cultural arts groups who have agreed to relocate to Main Street. More than $160 million in building contracts or renovations are underway (more than 200 dwelling units) by the private sector, including ground floor tenant space for cultural groups. Phase one construction on LID streetscapes begins March 2014.

,更多请至:

University of Arkansas Community Design Center and Marlon Blackwell Architect

客服

消息

收藏

下载

最近