查看完整案例

收藏

下载

△ Food City希望建立以城市为基础的食品生产模型,以应对食品危机和等等其他挑战。

Food City devises an urban-based food production model to address food insecurity and other challenges to resiliency.

Photo Credit: University of Arkansas Community Design Center

We have never seen food’s true potential, because it is too big to see. But viewed laterally it emerges as something with phenomenal power to transform not just landscapes, but political structures, public spaces, social relationships, and cities.” Carolyn Steel, Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives.

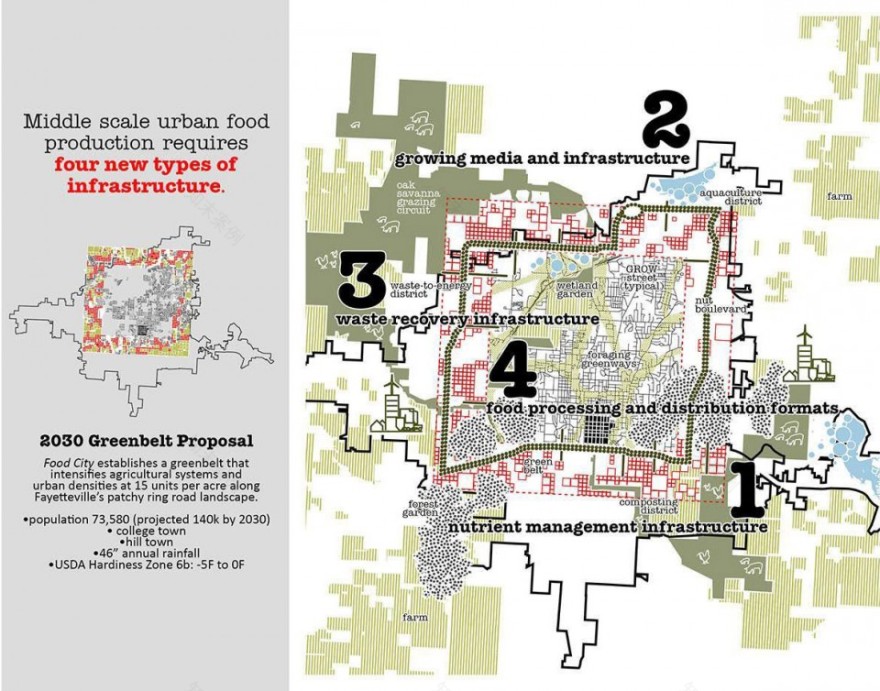

Goals and Objectives: Scenario Planning Toward More Robust Decision Making

What if Fayetteville’s projected growth enabled the city to sustain its food budget through a local urban agriculture network? Fifty percent of Fayetteville’s built environment projected to exist by 2030 has not yet been built as the city doubles its population of 73,000. Food City envisions a future based on resilient forms of urbanism where more than 28% of area children are food insecure (vs North Dakota’s 10%, the country’s lowest). While the large metropolis sponsors the most efficient carbon footprint per capita, moderate scale cities like Fayetteville are better equipped to evolve resilient food-secure environments given the interconnectedness and metabolic alignment among their natural ecosystems, infrastructure, and urban fabrics.

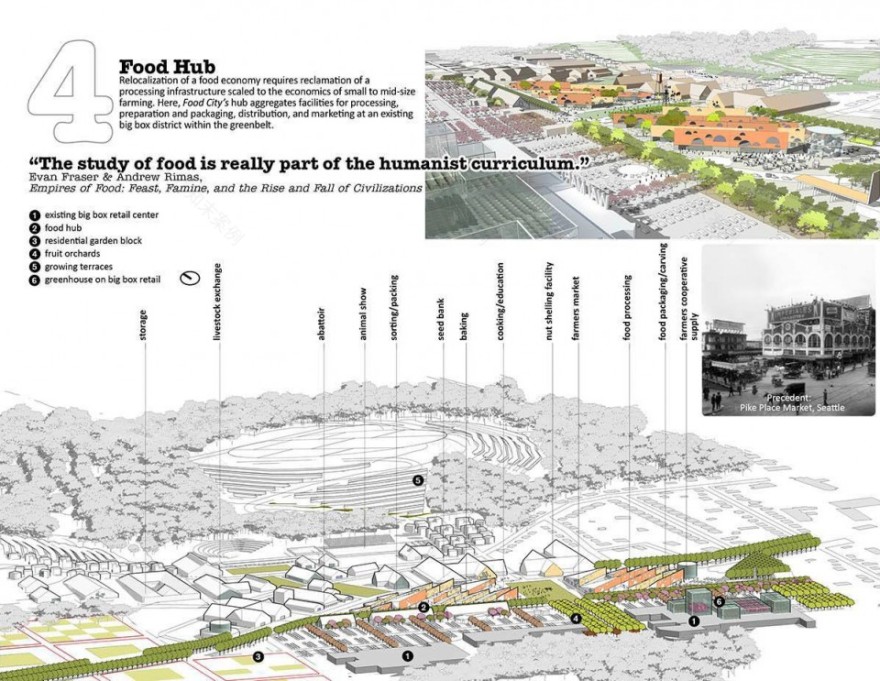

Funded by the Clinton Global Initiative, Food City devises a model transition vocabulary for establishing a food producing urbanism between that of the individual garden and the industrial farm. The proposal reclaims a “missing middle” foodshed that functions as an ecological municipal utility featuring green infrastructure, public growscapes, and urban spaces for food processing and distribution. Design solutions address municipal-scaled nutrient management through composting networks, integrated waste management utilities, deep litter farming, and aquaculture—all to build healthy soil structure and growing mediums, the basis of local farming. The scenario plan gives the city, local nonprofits, and the development community license to act on a complex and potentially disruptive development issue not amenable to the market-based process for procuring planning services. Examining urban food production as a driver of smart growth management has created a more robust decision-making culture among Fayetteville’s development interests, including a neighboring city that co-opted the issue to plan a regional food hub.

Food City formulates an agroecology of Five Urban Growing Guilds associated with niche functions: 1) permaculture/foraging landscapes, related to perennial landscapes hosted by existing woodlands; 2) farming and gardening requiring intensive management of annual landscapes; 3) GROW Streets (Gardened Right-of-Way) associated with street orchards and edible front yards; 4) pollution remediation landscapes that support safe urban growing; and 5) waste-to-energy districts that upcycle concentrated agriculture and urban waste streams.

The planning approach creates a successional framework for evolving recombinant forms of town and country, including novel suburban retrofits. Food City devises a set of agricultural urban real estate products value-added to the nineteen standard types financialized by Wall Street. By 2080, Food City will have evolved a highly networked agricultural urban mat seeded from a provisional greenbelt that simultaneously intensified scattered agricultural and urban fabrics.

Sustainability: Agroecology or Farming that Delivers Ecosystem Services

Food City proposes a regenerative urbanism that creates integrated loops from otherwise disconnected flows in energy, food, water, ecological, and financial systems. In addition to growing strategies, Food City integrates upcycling strategies in energy harvesting and waste management, a portfolio of water, soil, and conservation strategies, and hybrid settlement patterns that blend productive landscape systems and urbanism. Design solutions address municipal-scaled nutrient management issues through composting networks, integrated waste recovery utilities, deep litter farming, and aquaculture toward building healthy productive soils, which takes years. Farming and urbanism are recombined to deliver the 17 ecosystem services provided in all healthy ecosystems (per Robert Costanza et al., pollination, erosion control, water regulation/supply, nutrient cycling, disturbance regulation, soil formation, etc.).

Environmental/Social Data and Methods of Analysis

In their Preliminary Assessment of Fayetteville Food Security Measures (2012), ecological engineers characterized the caloric productive capacity of the Fayetteville area identifying two important planning parameters for developing locally based food production.

Per capita food demand in an industrialized nation will be 3500 calories per day in 2030 with 30 percent of the demand for animal products and the remaining 70 percent for plant products. While diet profiles vary culturally, human sustenance requires 25 percent calories from fat, 25 percent calories from protein, and 50 percent calories from carbohydrates. To meet this caloric demand Fayetteville will require 172 billion calories per year, entailing substantial amendments to its rocky soil structure. Most local soils lack robust nutrient compositions to support crop diversity—a primary benchmark of resiliency. Food City, therefore, proposes comprehensive nutrient upcycling at the municipal scale to recover organic nutrients lost or exported in open-loop systems (e.g., waste treatment, soil erosion, groundwater management, food export, etc.).

Fayetteville’s existing land area is 35,000 acres. An additional 162,190 acres or 1.25 acres per person (national average) would be needed to support beef production based on contemporary diets. Not all food production can be urbanized. If beef was removed from the equation and nutritional requirements were met through sources of protein other than beef, then a foodshed of 35,150 acres or 0.25 acres per person would be needed. The urban agricultural footprint necessary to support this scenario then would be equal to the city’s existing footprint of 35,000 acres. Food City assumes the latter scenario.

Role of Design and Consideration of Options: The Option of Local Food Production

Food City as a scenario plan visualizes the question of food security through design exercises that enhance the community’s decision-making processes about its future direction of growth. Food City doesn’t demand that everyone become a farmer. Rather, the intent is to recall urban relationships eliminated from the modern city that are necessary to once again accommodate the option of local food production. Food production constitutes a local economy and a local ecology, requiring a land use system that reconciles urban and landscape systems. The Five Urban Growing Guilds and agricultural urban real estate products constitute a transferable planning vocabulary for embedding agricultural capacity into urban settlement patterns at all scales.

Public Participation and Project Implementation

Besides the city’s Local Food Code Task Force, the project team worked with local growing and food distribution nonprofits (some established by the governor to address food insecurity) to formulate demonstration projects around community farms and edible parks (two starter urban farms have subsequently been built). The design team and nonprofits simultaneously worked with the city in 2013 to create enabling urban agricultural codes within the city’s land use framework. Food City is another tool in the statewide effort to marshal public-private alliances in correcting the misalignment between food production and consumer access by way of local food production. This partnership has also motivated the proposal for a humanities-based food curriculum at the state’s flagship university.

MORE:

University of Arkansas Community Design Center

,更多请至:

客服

消息

收藏

下载

最近